As a heavy metal fan I found it a real pleasure to watch Metal: A Headbanger's Journey. Sam Dunn's 2005 documentary is a fun, insightful look at my favorite genre of music and actually manages to do it justice. Dunn is not only a smart filmmaker but he's also a fan, and it shows in the final product.

As a heavy metal fan I found it a real pleasure to watch Metal: A Headbanger's Journey. Sam Dunn's 2005 documentary is a fun, insightful look at my favorite genre of music and actually manages to do it justice. Dunn is not only a smart filmmaker but he's also a fan, and it shows in the final product."Wonder had gone away, and he had forgotten that all life is only a set of pictures in the brain, among which there is no difference betwixt those born of real things and those born of inward dreamings, and no cause to value the one above the other." --H.P. Lovecraft, The Silver Key

Sunday, September 28, 2008

A review of Metal: A Headbanger's Journey

As a heavy metal fan I found it a real pleasure to watch Metal: A Headbanger's Journey. Sam Dunn's 2005 documentary is a fun, insightful look at my favorite genre of music and actually manages to do it justice. Dunn is not only a smart filmmaker but he's also a fan, and it shows in the final product.

As a heavy metal fan I found it a real pleasure to watch Metal: A Headbanger's Journey. Sam Dunn's 2005 documentary is a fun, insightful look at my favorite genre of music and actually manages to do it justice. Dunn is not only a smart filmmaker but he's also a fan, and it shows in the final product.Friday, September 26, 2008

Samwise the Brave: Examining the central hero of The Lord of the Rings

--Sam Gamgee, The Lord of the Rings

You don’t have to squint to find heroes in J.R.R. Tolkien’s The Lord of the Rings. Splashed across its pages are Aragorn, the uncrowned king in the wilderness, who walks the Paths of the Dead and claims his rightful position on the throne of Gondor; Gandalf, who bests the Balrog of Moria and confronts the Witch-King one-on-one; and Frodo, who suffers as the Ring’s bearer, carrying its weight into Mordor to liberate Middle-Earth from the darkness of Sauron. Theoden, Eowyn, and Faramir also spring immediately to mind. Aragorn and Frodo in particular can certainly be viewed and successfully argued as the central figure(s) in Tolkien’s tale.

But over the course of re-reading The Lord of the Rings I am more convinced than ever that its true hero is Sam Gamgee, without whom the quest to destroy the One Ring could not have succeeded. Though he’s no doughty man-at-arms like a Conan or Launcelot du Lake, by tale’s end Sam’s great deeds and noble sacrifices earn him a place of honor in the roll of great fantasy heroes.

Now, my line of thinking isn’t exactly original: Tolkien in one of his letters calls Sam “the chief hero” of the story, and many others have also made this connection. But certainly others have overlooked Sam because he doesn’t conform to traditional notions of heroism. He’s certainly not a great warrior who battles hordes of enemies, the archetype of the genre of fantasy known as sword and sorcery.

Perhaps it’s because I frequent a lot of Robert E. Howard and Dungeons and Dragons message boards, but it seems like larger than life heroes are the rage these days. Our current heroic archetypes include D&D with its player-characters as powerful supermen (4E, I'm looking at you), Harry Potter/The Belgariad and its ilk (seemingly normal people with great but latent magic powers), or sword and sorcery heroes inspired by Conan, mighty warriors capable of killing a half-dozen men in the afternoon and drinking the night away at the local tavern. Older archetypes include men like Achilles or Odysseus, men of action and martial prowess so extraordinary that they seem demigods among men.

Sam is a very different type of hero: a hobbit with no warrior skill who gets by solely on bravery and devotion to Frodo. Tolkien said his character was inspired by the British rank-and-file soldiers who served and fought and often gave their lives without fanfare in the trenches of World War I, expecting nothing and possessing only the hope of home at the end of it all (which is all Sam really wants). Said Tolkien in a letter, “My ‘Sam Gamgee’ is indeed a reflexion of the English soldier, of the privates and batmen I knew in the 1914 war, and recognized as so far superior to myself.”

Certainly Sam can’t compare with a Conan or a Fafhrd in terms of skill-at-arms. Like all hobbits he’s small in stature, possesses no skill with a blade, and is much more at home in a garden than on a battlefield. But Sam possesses undaunted courage when pressed, optimism in the face of impossible odds, and above all else an unshakeable call to duty to serve his master. When he throws himself into the waters of Parth Galen (despite the fact he cannot swim) in order to join Frodo’s seemingly suicidal quest into Mordor and emerges spluttering and half-drowned but with his will unshaken, we are witness to devotion of the rarest kind:

‘But I am going to Mordor.’

‘I know that well enough, Mr. Frodo. Of course you are. And I’m coming with you.’

The Lord of the Rings is very much a testament to the fact that even the greatest of men can’t solve all the world’s problems on their own. Galadriel’s comment that “hope remains while all the Company is true” (emphasis mine) is Tolkien’s belief writ large that alliances—not unilateral actions—are necessary for our long-term survival. Her words also prove to be prescient within the story: When the Fellowship fails and breaks up, Sam remains as Frodo’s only company on the long trek to Mordor. His presence, every bit as much as Frodo’s act of pity toward Gollum, allows the quest to succeed. It’s a difficult choice for Sam, especially after he peers into Galadriel’s mirror and sees the Shire being torn up and industrialized, and his father, his poor old gaffer, displaced. His decision to remain and sacrifice his personal desire to return home in order to serve the greater good (the destruction of the Ring) is the very essence of heroism.

Sam eventually is thrust into the hero’s role after the Fellowship breaks and he and Frodo trek to Mordor alone. I found myself cheering aloud (well, almost) when Gollum betrays Frodo to Shelob and attempts to kill Sam himself, and gets far more than he bargained for when Sam more or less kicks his ass:

Fury at the treachery, and desperation at the delay when his master was in deadly peril, gave to Sam a sudden violence and strength that was far beyond anything that Gollum had expected from this slow stupid hobbit, as he thought him. Not Gollum himself could have twisted more quickly or more fiercely.

But Sam’s real moment in the sun comes in Chapter 10 of The Two Towers, “The Choices of Master Samwise.” By all appearances Sam is too late to save his master who lies motionless, bound in cords, at the feet of Shelob—a huge, loathsome, horrifying creature from nightmare. But Sam does not pause, attacking the spider in a frenzy:

Then he charged. No onslaught more fierce was even seen in the savage world of beasts, where some desperate small creature armed with little teeth, alone, will spring upon a tower of horn and hide that stands above its fallen mate.

My favorite part of this epic battle is when Sam invokes the name of the goddess of beauty and light (“Gilthoniel A Elbereth!”) staggers to his feet, and is “Samwise the hobbit, Hamfast’s son, again.” He issues a challenge that might have made Clint Eastwood’s Man With No Name or Evil Dead’s Ash crack a smile:

“Now come, you filth!” he cried. “You’ve hurt my master, you brute, and you’ll pay for it. We’re going on; but we’ll settle with you first. Come on, and taste it again!”

Shelob, confronted with this three-and-a-half foot tall hobbit of the Shire, turns her ponderous, bloated body and heads for her hole, leaving a trail of fluid from the painful prick of the sword Sting.

But perhaps my favorite Sam moment is when he literally lifts Frodo on his back and carries him up Mount Doom:

‘I said I’d carry him, if it broke my back,’ he muttered, ‘and I will!’

‘Come Mr. Frodo!’ he cried. ‘I can’t carry it for you, but I can carry you and it as well.’

There’s no mistaking Sam as hero here, as at the very end of his endurance he somehow finds the strength to carry the literal weight of Middle-Earth on his stout back. I thought Jackson’s film captured this scene magnificently.

Yet Sam is not perfect. Tolkien in his letters describes him as having “a mental myopia which is proud of itself, a smugness (in varying degrees) and cocksureness, and a readiness to measure and sum up all things from a limited experience, largely enshrined in sententious traditional ‘wisdom.’” Sam’s biggest failure is indeed his lack of wisdom; specifically, he fails to notice Gollum’s act of repentance when the latter was about to abandon his scheme to send the hobbits to their death in Shelob’s lair. With a little kindness from Sam, Gollum perhaps could have buried his evil half and become Smeagol once again, but Sam tragically failed to recognize it (of course, you can argue that without Gollum’s attack on Frodo at the crack of doom, the Ring would not have been destroyed).

Is Sam a “fated” hero?

Tying into my previous thoughts on “fate vs. free will”, Sam’s actions and the circumstances that surround him walk a tightrope between his own free will and the larger forces at work in Tolkien’s world. Is Sam a simple, loyal hobbit who makes tough choices out of the goodness of his heart? Or is he fated to become a hero? I believe the answer is both.

For example, in “The Choices of Master Samwise,” Sam makes the difficult choice to leave Frodo’s body and carry on the quest alone. It’s perhaps his bravest act of all. But even as he walks down the tunnel “something” tells him his choice to leave Frodo’s side was wrong. When the orcs find Frodo he realizes it: “He flung the Quest and all his decisions away, and fear and doubt with them. He knew now where his place was and had been: at his master’s side, though what he could do there was not clear.”

The implication here is that the orcs’ arrival was an act of fate, not chance, and that some higher power perhaps intervened on Sam’s behalf. Certainly the outcome of the story would have been far different had Sam soldiered on alone, for as we later see, no man or hobbit acting alone can willingly destroy the Ring.

I also wonder whether Sam was in fact chosen for his great task by Gandalf. Was fate at work in the seemingly chance act of Sam eavesdropping at Frodo’s window at Bag End and getting caught by Gandalf? Did Gandalf send Sam with Frodo only to punish him? Or did Gandalf send Sam because (as one of the Maiar) Gandalf knew at some level that Sam could play a vital role in the outcome of the quest?

Given what we know of both Gandalf and Middle-Earth's cosmology, the latter seems much more likely.

Monday, September 22, 2008

Sanitized fairy tales: News story exposes modern trend of bland safeness

Fear of fairy tales: The glossy, sanitized new versions of fairy tales leave out what matters: The scary parts.

Weiss' article lays out the case that something important is lost when a child's introduction to fairy tales comes in whitewashed form, and the old classic tales are denuded of anything mildly scary. Writes Weiss:

In toys, movies, and books, the old fairy tales are being systematically stripped of their darker complexities. Rapunzel has become a lobotomized girl in a pleasant tower playroom; Cinderella is another pretty lady in a ball gown, like some model on "Project Runway."

Weiss adds that what makes classic fairy stories timeless are the difficult and often dark elements they contain, which often provide instructive allegory or socially relevant commentary.

I couldn't agree more. As a father of two children I've seen a lot of these kid-friendly versions of the old tales, most of them by Disney. The new rage these days is Disney Princesses, which feature the classic princesses from fairy tales (Cinderella, Snow White, Hans Christian Anderson's Little Mermaid, etc.) living together and spending their days overcoming safe, mundane, and rather trivial obstacles. The result is that kids are entertained, but not challenged. Meanwhile, Disney makes millions selling product-tie ins like costumes, vanity sets, and sanitized books and videos. Writes Weiss:

When the stories intersect with commerce these days--whether in children's books or the endless barrage of toys--they can quickly get reduced beyond recognition. It's easier to sell a Rapunzel playset, after all, as something entirely cheery and safe.

Some parents I suppose will argue that they don't want to expose their children to anything that might potentially scare or unsettle them. I won't argue with that; it's their choice. But the answer is not in stripping classic fairy tales of vitality and meaning. Let them watch Barney or Sesame Street instead. These are fine alternatives (well, Sesame Street is, Barney is Chinese water torture). Although I do think that children are given far too little credit for their ability to distinguish fact from fiction, and fantasy stories from reality. They're pretty smart. For decades and centuries kids grew up on these stories, and most of us turned out all right.

My oldest daugher is six and I plan on reading her The Hobbit soon. Suffice to say that I won't be reading a safe, sanitized version in which Thorin doesn't die, or Gollum becomes a slapstick comic device instead of a slimy, corrupted creature eyeing Bilbo as a tasty meal.

Saturday, September 20, 2008

Shelob: A frightening, ancient evil

He may not be Steven King or Edgar Allen Poe, but J.R.R. Tolkien manages to pack a couple scares into The Lord of the Rings. Two chapters in particular send a chill down my spine: One is the "Passage of the Marshes," which I discussed in a recent post, and the other is "Shelob's Lair."

He may not be Steven King or Edgar Allen Poe, but J.R.R. Tolkien manages to pack a couple scares into The Lord of the Rings. Two chapters in particular send a chill down my spine: One is the "Passage of the Marshes," which I discussed in a recent post, and the other is "Shelob's Lair."Re-reading this latter chapter made me remember how loathsome a monster is Shelob. She is truly horrifying, a monster that makes Pennywise's true form in King's It seem like a daddy longlegs in comparison. She is old, old enough to darken Middle-Earth before Sauron arrived on the scene, and bloated from drinking the blood of Elves and Men. Tolkien says she cares not for wealth or power, but spends all her time brooding on her next feast. "For all living things were her food, and her vomit darkness," he writes. That's about as nasty and explicit as Tolkien gets.

More dreadful is the knowledge that Sauron knows of Shelob and feeds it with orcs and prisoners:

And sometimes as a man may cast a dainty to his cat (his cat he calls her, but she owns him not) Sauron would send her prisoners that he had no better uses for: he would have them driven to her hole, and report brought back to him of the play she made.

"Play she made?" Jesus, I don't know what's worse--being paralyzed with poison and eaten alive by a monstrous, reeking, millenna old spider, or the thought of Sauron listening to such tales with glee.

Tolkien does a masterful job building up the horror in "Shelob's Lair," primarily by engaging other senses than sight in the reader, particularly smell. As Sam and Frodo approach Torech Ungol (Shelob's Lair), they catch scent of its foul reek, "as if filth unnameable were piled in the dark within." This is a rancid, foetid stench that can only belong to some great, millennia-old carnivore.

Inside Shelob's lair the air is still, stagnant, heavy, and any sounds Frodo and Sam make fall dead. It is pitch black, so dark you cannot see your hand though you hold it inches from your face. The evil and foulness are palpable, and Tolkien describes how a great fear and dread is upon the hobbits, though they do not know its origin. The oppression is so great that Sam and Frodo clasp hands in the darkness.

Our first encounter with Shelob not visual, but conveyed through her awful sounds, described by Tolkien as, "Startling and horrible in the heavy padded silence: a gurgling, bubbling noise, and a long venomous hiss." Then come the eyes, two great clusters of many windows. "Monstrous and abominable eyes they were, bestial and yet filled with purpose and with hideous delight, gloating over their prey trapped beyond all hope of escape."

When Tolkien finally draws aside the curtain for the big reveal, Shelob is every bit as noisome as my mind had prepared her to be. I think there's something particularly hideous about spiders as a species, and Shelob is truly the worst:

Hardly had Sam hidden the light of the star-glass when she came. A little way ahead and to his left he saw suddenly, issuing from a black hole of shadow under the cliff, the mostly loathly shape that he had ever beheld, horrible beyond the horror of an evil dream. Most like a spider she was, but huger than the great hunting beasts, and more terrible than they because of the evil purpose in her remorseless eyes. Those same eyes that he had thought daunted and defeated, there they were lit with a fell light again, clustering in her out-thrust head. Great horns she had, and behind her short stalk-like neck was her huge swollen body, a vast bloated bag, swaying and sagging between her legs; its great bulk was black, blotched with livid marks, but the belly underneath was pale and luminous and gave forth a stench. Her legs were bent, with great knobbed joints high above her back, and hairs that stuck out like steel spines, and at each leg's end there was a claw.

Sam's confrontation with Shelob is also one of my favorite scenes, and it is here and in his actions subsequent to Frodo's poisoning and capture that he emerges as a great hero in the rolls of fantasy literature.

Wednesday, September 17, 2008

War and death come to Middle Earth

--Faramir, "The Two Towers"

Although regarded as high fantasy (and thus conflated with "escapism," often by those who should know better), J.R.R. Tolkien's The Lord of the Rings is also a treatise on war. Books 3 and 4 of Tolkien's tale (The Two Towers) shift the focus of the story from that of the adventures of the Fellowship to a broader conflict brewing in Middle Earth. The company emerges from the dark pit of Moria and the bright woods of Lorien only to be swept up in the machinations of Saruman and the great battle at Helm's Deep.

In my re-reading of The Lord of the Rings I recently passed through the vast bogs and fens which lie between the Emyn Muil and Mordor. This wide stretch of trackless, treacherous land is home to the Dead Marshes, named for the spectral corpses of fallen men, elves, and orcs that lie beneath its muck and dark waters. At one time their bodies lay on the dry Dagorlad, the site of a great months-long battle of the second age of Middle Earth. In this battle the Last Alliance of elves, men, and dwarves fought Sauron's forces at the gates of Mordor. The forces of good prevailed as Isildur cut the One Ring from Sauron's hand, but only after tremendous loss of life on both sides. Gradually the swamp spread, covering the land and the bodies of the slain.

Tolkien wrote in a letter that he drew his inspiration for the landscape of the Dead Marshes from experiences in the Somme, but it's no great stretch to speculate that this terrible battle made an impact in other, more profound ways on The Lord of the Rings. In the first day of the Somme the British suffered their worst loss of men in a single day in British history; 57,000 casualites, including 19,000 young men whose lives were snuffed out like candles in a hail of German machine-gun fire and shrapnel. Among those to die in the Somme were Tolkien's good friends Rob Gilson and G.B. Smith (for a compelling and complete recounting of Tolkien's wartime years and its influence upon his writings, I heartily recommend Tolkien and the Great War: The Threshold of Middle Earth, by John Garth).

In the Dead Marshes Frodo, Sam, and Gollum come face-to-face with death as the great fear--that it is simply the end, and that there is no immortal soul. Our lives are simply snuffed out when our bodies fail or are destroyed. All men, good and evil alike, are mingled together in the common lot of corruption, the grave, where good deeds in life are not rewarded by the eternal hereafter--because there isn't one. The images of the dead in the pools reflect this horror, notes Frodo:

They lie in all the pools, pale faces, deep deep under the dark water. I saw them: grim faces and evil, and noble faces and sad. Many faces proud and fair, and weeds in their silver hair. But all foul, all rotting, all dead. A fell light is in them.

In another passage from The Two Towers that I had forgotten, Sam, Frodo, and Gollum manage to find a brief respite in the land of Ithilien, still fair and flowering even though it has fallen beneath the shadow. But this peace is only an illusion, a respite: When Sam leaves the path to examine the trees, he stumbles on a ring still scorched by fire, and in the midst of it finds a pile of charred and broken bones and skulls.

Tolkien witnessed too much of this senseless loss of young life in his experience during the Somme, which explains why death weighs heavily on his mind in The Lord of the Rings. Elves alone have the gift of immortality, but men are mortal and "doomed to die." As men dwindle from the greatness of their elder days so too are their lifespans reduced.

Yet The Lord of the Rings is also infused with heroic men and martial victories. Garth posits that Tolkien did not believe that the sacrifice of young men's lives was a waste, if given for the right reasons. Writes Garth: "It [The Lord of the Rings] examines how the individual's experience of war relates to those grand old abstractions; for example, it puts glory, honour, majesty, as well as courage, under such stress that they often fracture, but are not utterly destroyed."

Tolkien personified his feelings about concepts like glory, honour, and courage in the peoples of Rohan. Rohan is at constant war with the orcs and wild men, and like the Dunedain must remain ever alert, guarding against encroaching evil. They believe that death on the battlefield, while sorrowful, is never in vain as long as their acts are remembered. Thus the wistful (and my personal favorite) bit of Tolkien poetry, the Lament for Eorl the Young:

Where now the horse and the rider? Where is the horn that was blowing?

Where is the helm and the hauberk, and the bright hair flowing?

Where is the hand on the harpstring, and the red fire glowing?

Where is the spring and the harvest and the corn growing?

They have passed like rain on the mountain, like a wind in the meadow; The days have gone down in the West behind the hills into shadow.

Who shall gather the smoke of the dead wood burning,

Or behold the flowing years from the Sea returning?

This piece captures Tolkien's ambivalent feelings about war. The poem on the one hand portrays the magnificence of Eorl, resplendent in his war gear and the full flower of his years, using the symbolic language of spring and harvests and growing corn. But the song also mourns his death, asking again and again "Where has he gone?" in a question that cannot be answered. Eorl's passing leaves no trace, like a whisp of smoke. For the living only his memories remain.

The Riders of Rohan remember their dead with songs like these and through the simbelmyne, a small white flower which grows on their graves and tombs. According to the Encyclopedia of Arda, "simbelmynë is translated as 'Evermind': a reference to the memories of the dead on whose tombs the flower grew."

Tolkien does not take war lightly and the men of Rohan, though portrayed in a sympathetic light, are not his ideal. That place is held by Faramir, Tolkien's portrayal of man at his best. Faramir sees war with a keen eye, and tells Sam and Frodo that the high men of Numenor, of which he is a descendant, have "fallen" and are becoming like the Rohirrim, loving valor for valor's sake: "Yet now, if the Rohirrim are grown in some ways more like to us, enhanced in arts and gentleness, we too have become more like to them, and can scarce claim any longer the title High...For as the Rohirrim do, we now love war and valor as things good in themselves, both a sport and an end."

Tolkien's clearest view on war is revealed in a famous passage in which Sam views the body of a dead soldier from the south, slain at his feet by arrows from Faramir's men in the woods of Ithilien:

He was glad that he could not see the dead face. He wondered what the man's name was and where he came from; and if he was really evil of heart, or what lies and threats had led him on the long march from his home; and if he would not really rather have stayed there in peace.

In other words, war is terrible and of last resort, and slain foes are, in the end, just men--and therefore to be pitied. War is necessary when "destroyers" like Sauron or Hitler would impose their will on the free peoples of the world, but it is a duty to be carried out, not glorified. It brings with it too much death and sorrow. In his famous foreward to The Lord of the Rings, Tolkien wrote:

One has indeed personally to come under the shadow of war to feel fully its oppression; but as the years go by it seems now often forgotten that to be caught in youth by 1914 was no less hideous an experience than to be involved in 1939 and the following years. By 1918 all but one of my close friends were dead.

Tolkien never forgot the loss of Gilson and Smith, nor the Somme. At some level it fed into his passion for language and myth, providing fertile ground for a great tale. We have The Lord of the Rings to thank.

Sunday, September 14, 2008

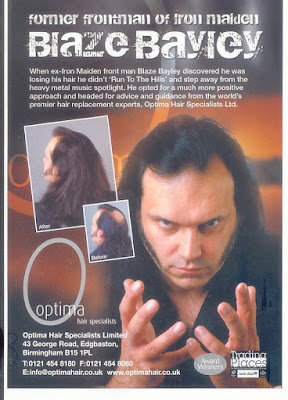

Run to the Hills: Bayley back in the news (for his hair)

Somewhere I can hear the singing, "I'm running out of my hair, I'm running out of it..."

I can't rank on Blaze Bayley too much, considering that the photo of his bald spot pre-treatment looks a lot like mine, only smaller. But this ad from Mojo Magazine was too good to pass up. Love the posed hands, as if he were about to invoke some sorcerous power.

Oh, and the sideburns too.

Thursday, September 11, 2008

The Road: Exploring Tolkien's grand metaphor

Down from the door where it began.

Now far ahead the Road has gone,

And I must follow, if I can,

Pursuing it with eager feet,

Until it joins some larger way

Where many paths and errands meet.

And whither then? I cannot say.

As a kid one of the many things I loved about The Hobbit was its maps. The map of the Wilderland just inside the front cover of the book (see picture above) had a dotted line that crossed the Misty Mountains, followed the Old Forest Road, and, if you turned North when you reached the River Running, took you past the Long Lake and to the foot of the Lonely Mountain. I recall tracing the journey with my finger and at times letting it wander (not too far) into Mirkwood on either side.

The Road as life

Tolkien says that the Road can sweep you off your feet, implying that it has an element of wildness and chance about it. It can take you to places you never expected. You may face hardships and perils or death in a foreign land. You may find great wealth, or the last refuges of magic, in realms where time seems to stand still.

But the Road always starts with a simple choice, and that is the decision to set your foot upon it. It starts with humble beginnings, from a single door in Bilbo's case, but if you follow it long enough it will take you to an intersection of many paths and errands. This very much parallels the course of a life, in which a child has but a few options but eventually encounters the many freedoms (and perils) that come with adulthood.

In his walking song Bilbo cannot say where the Road eventually leads, because eventually choice intersects with chance. We can choose our own direction on the Road, for good or ill.

In my "normal" suburban life even I feel a tinge of fear and thrill of the unknown when I step onto the Road and leave my driveway on some long business trip, of which I typically take at least two a year. And I'm always amazed and relieved to find when, after boarding a jet plane and traveling 3,000 miles across the entire country and back again, I find myself once again at home with my family.

It may not be the Misty Mountains or Mordor but it's about all the excitement I can handle.

The Road as death

Of course, eventually we all must reach the end of the Road. Tolkien offers four versions of Bilbo's walking song in The Lord of the Rings; each time the teller (alternating between Bilbo and Frodo) is further along in the Road of his life.

The first time we hear Bilbo's song it's the quote I started with above, and it's full of energy and anticipation of the journey. The second time, Frodo sings the song and he has begun the long trek to Mordor. In place of "eager feet" we get "weary feet." He is feeling the weight of his great task, just as we feel the adult weight of jobs, responsibilities, and age.

In "Many Partings," we hear the song for a third time. Bilbo knows his traveling days are winding down when he sings:

The Road goes ever on and on

In The Road to Middle Earth, author Tom Shippey states that Bilbo here is equating the lighted inn with Rivendell, which is his literal next stop, but that he is also referring to his own death.

In "The Grey Havens," the final chapter of The Lord of the Rings, Frodo sings Bilbo's old walking-song one last time, though the words have changed much:

In other words, there is a new Road to take at the end of our lives. It is a road hidden to mortal men, perhaps always under our noses ("oft have passed them by") but invisible to our senses. No living man (nor hobbit) has ever started down this road.

According to Tolkien's cosmology, Middle-Earth was once flat, and you could reach the Undying Lands if you sailed far enough out to sea. But the Numenoreans abused this opportunity, and as punishment the Creator gave Middle Earth its present round shape. The straight Road was lost, and now only the elves can find the Grey Havens.

Man has a different final Road to take than that of the elves, one that Tolkien hints in his cosmology may lead his soul, freed from his body, back to the Creator.

My own Road

I'm glad to say that, right now, my Road runs straight through Middle Earth (right now I'm listening to The Lord of the Rings as I drive Route 95/114 to work; hardly Bilbo's garden path or the East-West road running out of the Shire, but it will have to do). Middle-Earth is becoming a well-trodden and familar path but I never tire of taking the trip.

If there is an afterlife, I hope with all that's in me that I will awake at the end of my Road to find myself in Meduseld, the golden hall of Theoden, my current stop in my latest re-read of The Lord of the Rings. Even better, perhaps I may one day find myself enjoying a fine beer at The Prancing Pony, listening to the locals tell a queer tale about a hobbit from the Shire and his companions who fell in with a mysterious ranger from the North. Time will tell.