(Warning: Spoilers)Utopias cannot survive contact with the world of commerce. It’s a message delivered in brutal fashion in the catastrophic ending of George Romero’s Knightriders (1981). Idealism meets the hurtling steel of a freight truck, alternative counterculture going under the wheels of the unstoppable economic engine of the 1980s.

The outcome is predictable and sad. But the leadup and the message of the film is magic.

Weird and flawed, too on the nose perhaps with heavy-handed messaging, Knightriders nevertheless succeeds. It’s unpredictable, meaningful, wonderfully anti-establishment, and utterly singular.

The film opens with a knight (Ed Harris) waking up in a forest, naked and in the arms of his paramour. He kneels and prays over the hilt of his sword, enters a nearby pool to bathe … and proceeds to beat his back with a branch in what we can only presume to be some sort of purification ritual.

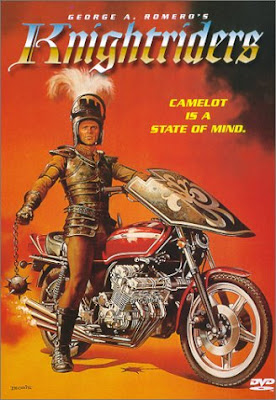

Right then you know you’re in for an offbeat movie. And if you had any doubts Knightriders goes straight off the deep end when instead of a horse Harris climbs on a motorcycle and rides back to “Camelot.”

Romero apparently got the idea for Knightriders from the violent medieval reenactments hosted by the Society of Creative Anachronism (SCA). He had planned on horses but producer Sam Arkoff told him to put his knights on motorbikes. The rest is history. Despite the obvious anachronisms it makes painstaking efforts toward medieval realism, from the forging of weapons, romance, and chivalric oaths sworn in fealty to a king, who is really only a man (and a flawed one at that) full of grand ideas and a vision of something better.

Knightriders engages with the myth of King Arthur in a very unique way, demonstrating the extreme malleability of the old stories. It skips the “historical” Arthur of the 5th/6th century and the romantic late medieval-ish setting of Excalibur and instead leaps straight into 1980. There are no knights, no nobles, no real king. The story instead follows a troupe of traveling entertainers who put on a combination renaissance fair and tournament, complete with jousting and full-on melee conducted by knights riding motorcycles. At its head is Billy (Harris), a stand-in for Arthur. He is the heart of this comic but earnest ragtag group of misfits.

Instead of Camelot Billy’s “kingdom” is a commune of outsiders, all wanting something different than the 20th century has to offer. It’s got some similarities with the hippie communes of the 60s, perhaps the last gasp on the verge of the decade of excess.

It wasn’t at all what I was expecting. I of course know Romero from Night of the Living Dead and its various sequels, and so I thought I might be getting ultraviolence, apocalypse, bloodshed. Knightriders is none of the above. There’s plenty of action, of course (the stunts are fantastic and I winced at a couple of the crashes--stuntmen hit the ground HARD. These guys were not making an easy paycheck). But its basically a character drama spread across a large troupe of actors. All of Romero’s old cronies are in the film … as I was watching every five minutes I was like, “wait, there’s the guy from Dawn of the Dead, and another guy from Dawn of the Dead. That’s the guy from Day of the Dead! Wait is that a Stephen King cameo?” (answer—yes.) Tom Savini plays a major role, not a villain but a foil to the king, and who knew—Savini can act. It’s got an interesting Merlin too, a dude with some medical training but equal parts witch doctor, harmonica playing savant, and prognosticator.

It’s amazing Knightriders ever got made, and unsurprisingly it was a commercial flop. Harris admits in a relatively recent interview that while he remains a fan he knew it was destined for obscurity. It’s too odd and offbeat, non-genre, and the intended audience is unclear. Truth be told it’s also flawed. Some of the acting is, to be charitable, pedestrian. The dialogue in many places is stilted. It’s at least 30-40 minutes too long and badly in need of an edit. It meanders and threatens to lose the thread of story.

But I can deal with these imperfections, even its deep and abiding flaws, for what we did get. Imperfection is the way of the world. The courage of knights wavers, their honor and fealty are tested by fortune and fame and lust, and often fail. This film does not fail, and for what it lacks in technical artistry it succeeds through heart. I can think of very few films as earnest and sincere. Romero set out to make a statement about the pressures to sell out vs. staying true to your art, and of the extraordinary difficulties of leading a principled life. Of living a values-led life, to whatever end.

I felt a deep stir of emotion near the end of the film when Harris/Billy/Arthur sees himself not on a bike, but a horse, galloping off on some quest through green lands in a better place. He passes on his legacy in the form of a sword, handing it to a wide-eyed young fan who wanted only an autograph but got much more.

Even if we cannot ever experience earthly utopia the elusive search continues. As long as nonconformists and artists and the disaffected yearn for something more, Camelot beckons.