|

| T-800s like it here... but people too. |

Unfortunately some of it appears to be robots, likely using my posts to train LLMs. But robots are only part of the story. There are also a lot of fine folks who seem to like what I have to say here on the Silver Key. Lots of returning visitors, lots of comments. For which I remain very grateful.

I’ve got a lot to be grateful for on the writing front in 2025.

2026 will be the year of my heavy metal memoir. I spent a lot of time working on it behind the scenes. I shared it with three readers who appear in it and have taken their advice into consideration. Made a few changes. Re-read it after 3 months and rewrote quite a bit.

The writing is done, I can’t make it any better nor tell the story I want to tell any more effectively. Next will be editing and cover design.

I’m in the process of helping my friend Tom Barber publish his memoir via Kindle Direct Publishing. I can’t wait to share more details about Tom’s book, which details the depths of his alcohol addiction, his travels out west, all lavishly illustrated with his own artwork.

KDP is pretty easy to use and I’m near certain I will be using the same platform for my book.

It was a productive year for me on The Silver Key. This post is my 89th, the most I’ve published in a year since 2022, and my fourth highest annual output all-time. And as noted, traffic went through the roof.

People are somehow still visiting this archaic corner of cyberspace. As of this writing (Saturday, Dec. 20) I’ve had 71,000 views in 2025, up from 45,000 in 2024 and 29,000 in 2023. I expected to see traffic decline as folks use AI to find answers or information without going out to websites, but that’s not the case here.

I published broadly on heavy metal, sword-and-sorcery, reading trends, Arthuriana, and the war for our attention. All topics that interest me. All seemed to resonate.

My most popular post by far was a guest blogger writing about Rob Zombie.

Let’s take a look at the 20 most popular posts of 2025.

- An interesting personal insight into Moorcock’s inspirations (733 views). I learned something new about the author of Elric and Corum during this podcast interview—his father left the family when Moorcock was quite young, and the experience left him with abandonment issues and separation anxiety. Could this have been a formative influence on his writing?

- Celtic Adventures wrapup and on into Cimmerian September (760 views). I’ve read 40 books in 2025 including DMR’s Celtic Adventures. Highly recommend this title, if for nothing else than John Barnett’s “Grana, Queen of Battle.” A unbelievably cracking good bit of historical adventure written in 1913.

- Rest in Peace James Silke (775 views). The author of the Death Dealer series left us in February, age 93. That reminds me I need to read and review book 4, Plague of Knives. As I’ve noted these are so bad they cross back over to good territory.

- We're living in an outrage machine (776 views). I’m not a conspiracy theorist but I can say with certainty that most of the problems we have are not as large and certainly not apocalyptic as you’ve been led to believe by the media. Rather, your attention is monetized and fear and outrage sells.

- The Empress of Dreams—an (overdue) appreciation of Tanith Lee (776 views). I’ve never given Tanith Lee her just due and this collection from DMR books reminds me I need to read more of her stuff. Master stylist and atmosphere-ist.

- Rest in Peace, Howard Andrew Jones (783 views). Sad and terrible news about HAJ, who was taken from us far too early. His works will endure.

- The Ring of the Nibelung/Roy Thomas and Gil Kane (791 views). I’m glad I picked up this wonderful graphic novel by a pair of comic book greats. Recommended as an easily digestible entry point to Richard Wagner’s classic opera.

- Of pastiche and John C. Hocking’s Conan and the Living Plague (797 views). Anything I write about Conan or Robert E. Howard performs well. This is one of the better pastiches I’ve read, and here I weigh in on John C. Hocking’s book and what I like to see in pastiches in general.

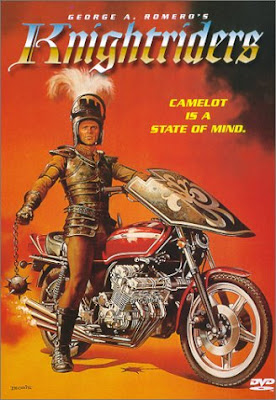

- Knightriders, a review (817 views). As a fan of all things King Arthur I can’t believe I’ve never watched this odd little film about modern “knights” on motorcycle horseback. Quirky and flawed but unique and recommended.

- Cold Sweat, Thin Lizzy (855 views). I continue to say that Thin Lizzy has been unfairly pigeonholed as a one hit wonder. Forget The Boys are Back in Town, listen to Cold Sweat. It rocks.

- Revisiting H.P. Lovecraft's "The Silver Key" (927 views). Wherein I revisit the story that gave this blog its name. There is no cause to value material fact over the content of our dreams.

- The Acts of King Arthur and His Noble Knights by John Steinbeck, a review (1033 views). I finally got around to reading Steinbeck’s treatment of the Athurian myth. Sadly unfinished but definitely worth reading.

- Goodbye to Romance: Reflections on Black Sabbath, Back to the Beginning, and the end of the road (1036 views). Another sad loss this year; the death of Ozzy Osbourne and the end of the first heavy metal band. Am waiting on the release of their final concert on DVD.

- Robert E. Howard, The Life and Times of a Texas Author (1039 views). Kudos to my friend Will Oliver on writing what may well prove to be the definitive biography of Robert E. Howard. A heroic amount of research. Pick this one up.

- Martin Eden (1909), Jack London 1083 views. Speaking of Robert E. Howard, this great story by the great Jack London contains many striking parallels to his life. It's an incredibly powerful book on its own merits.

- Reading is in trouble … what are we going to do about it? (1084 views). Reading is in serious decline and it saddens me. I don’t want to live in a world where we have no attention span and consume content no longer than Tweets and short-form video, though that is on our doorstep. Keep reading, and read to your children.

- Paper books are better than digital: Five reasons why (1085 views). I’m still a paper-only reader, don’t even own a kindle. One day that may change… but it is not this day.

- Bruce Dickinson at the House of Blues, Boston MA Sept. 11, 2025 (1182 views): Fantastic concert by the seemingly ageless singer of Iron Maiden, whom I had ever seen perform solo until this fall. Tears of the Dragon nearly brought me to tears.

- Disconnect (1423 views). The best remedy for many of the above ills is to take a technology detox (except for coming to the Silver Key). Also RIP Robert Redford.

- Celebrating Rob Zombie, graphic artist, at sixty (4,529 views) Guest poster Deuce Richardson stole my thunder with the biggest runaway post of the year. Why did this one outperform? Its well written, about a famous performer … but I also suspect it’s because Deuce had me include so many images of Rob's art. These show up in searches and drive traffic. Something for me to consider in my own posts. Either way, nice job Deuce.

***

Anyway, if you’ve gotten this far thanks for reading the blog, today and all year long. I always welcome your comments and suggestions.

Merry Christmas and I wish you a very fine 2026.