I've got a hell of a story to tell that I'm working on for the blog. Will be a few more days. Stay tuned.

"Wonder had gone away, and he had forgotten that all life is only a set of pictures in the brain, among which there is no difference betwixt those born of real things and those born of inward dreamings, and no cause to value the one above the other." --H.P. Lovecraft, The Silver Key

Friday, September 11, 2020

Friday, September 4, 2020

Farewell to Charles Saunders

Word spread on Facebook last night that Charles Saunders, author of Imaro, has passed away. It is being reported he died in May. Odd that an obituary search turns up empty.

Let's hope it may be a rumor, but it does not appear that way. Author Milton Davis, who continued in Saunders' "Sword-and-Soul" tradition, broke the news, and many authors, friends, and peers have chimed in since.

Imaro and its subsequent volumes deserves a longer post than I have time for at the moment, but I consider these terrific works of sword-and-sorcery. If not at the level of Howard/Leiber/Moorcock/Anderson, they rank up there with Henry Kuttner, Karl Edward Wagner, David Drake, and many other fine authors.

I regret not contacting Saunders when I had the chance to let him know how much I enjoyed his work. Nyumbani, Saunders' fantastic parallel of Africa, is a rich and sharply realized setting worth exploring, and Imaro is a memorable character with a dark past whose relentless search turned inward, far more than most sword-and-sorcery heroes. As a black author working in a largely white field, Saunders was a pioneer and penned many thoughtful essays on his complex relationship with fantasy fiction and sword-and-sorcery ("Die Black Dog!" is worth seeking out). His stuff absolutely deserves a bigger following. The late Steve Tompkins of The Cimmerian website was one of Saunders' biggest champions and found a rich, mythic layer to the Imaro cycle.

Rest in peace.

Sunday, August 30, 2020

Masculinity in S&S? It’s complicated

Sword and sorcery is strongly masculine and appeals to men. We can see this same ethos in the Arnold Schwarzenegger movies of the 1980s and early 90s. Take a look at this scene from Predator and ask yourself what it plays to.

|

| The most manly handshake ever, bar none. |

And then ask yourself, is this cool? Is it OK to like this?

My answer is an emphatic hell yes.

Men who read S&S tend to like fictional depictions of violence and

strength. As

I’ve said elsewhere, dynamism, power, and muscular strength are among the

elements that draw me to the work of Frank Frazetta, for example.

Make no mistake: I love this stuff. I was drawn to it as a

kid, and inspired to pick up weights to try to look like my heroes of the

comics and silver screen. Today I continue to champion and defend it. I push

back, hard, against censorious critics who want this type of fiction

memory-holed. You can pry my sword-and-sorcery from my cold, dead fingers.

There’s a reason I and if I daresay the broader “we” are drawn to tales

featuring swordplay, bloodletting, and fast-paced action. These stories tap

into the same psychological wellsprings and biological impulses that help explain

our love for professional football, boxing, and strongman sports.

Sword-and-sorcery is loaded with beefcake and masculine

heroes. Here is a typical description of Conan, from “The Devil in Iron”:

As

the first tinge of dawn reddened the sea, a small boat with a solitary occupant

approached the cliffs. The man in the boat was a picturesque figure. A crimson

scarf was knotted about his head; his wide silk breeches, of flaming hue, were

upheld by a broad sash which likewise supported a scimitar in a shagreen

scabbard. His gilt-worked leather boots suggested the horseman rather than the

seaman, but he handled his boat with skill. Through his widely open silk shirt

showed his broad muscular breast, burned brown by the sun.

The

muscles of his heavy bronzed arms rippled as he pulled the oars with an almost

feline ease of motion. A fierce vitality that was evident in each feature and

motion set him apart from common men; yet his expression was neither savage nor

somber; though the smoldering blue eyes hinted at ferocity easily wakened.

I’ll stick my neck out a bit, risk the critical axe of politically

correct criticism, and say that as a result of its emphasis on violence and

power, sword-and-sorcery appeals to boys and men, in far larger quantities than

women.

But like life, art, and politics, even sword-and-sorcery is

not this simple.

Saturday, August 22, 2020

The best heavy metal guitar solo ever

I'm not qualified to render this judgement. I've got the time in to make an educated guess, as I've been listening to heavy metal since the mid-1980s, some 35 years I'd guess. But what I lack is the required breadth. I'm not a big fan of death metal, or black metal, or doom, or some of the other peripheral subgenres, and so can't speak to any solos that might exist in these far-flung corners of metal. Nor was I ever a fan of the true guitar virtuosos. I admire and respect the craft of the Steve Vais, Yngwie Malmsteins, and Joe Satrianis of the world, and admit they are probably the most talented guitarists to come out of metal, but I find I lack an emotional attachment to their music that keeps me from being a fan.

Most damning of all I don't play guitar. I cannot tell you what makes one solo better from another from a learned musician's perspective, and I lack the technical vocabulary to analyze music properly.

So to make a long story short your mileage may very well differ.

But for me, my favorite heavy metal guitar solo and the one that continues to leave me speechless with wonder is Marty Friedman's solo in "Tornado of Souls." I appreciate guitar solos that don't insist upon themselves. I love it when they fit the song, take off from a logical place and return to the rhythm. Friedman's solo almost breaks that spell, but does not.

I recommend not jumping immediately to 2:10 where the madness starts to build, or 3:09 where it becomes a solo proper, 3:28 where it blasts straight up into the stratosphere and parts beyond, or 3:48 where you're like, "what the fuck?" Do it if you must, but realize that this solo works best as the orgasmic culmination of an awesome song. It's worth the 5 minute investment. His skill and artistry and sound are evident right from the electric shocks of the opening notes.

If you're a metal fan and somehow have missed this one, I beg you to

rectify that right now. For non-metal fans who appreciate great guitar work, I

realize that Dave Mustaine's voice can be off-putting, but don't let

that stop you. Just listen.

Wednesday, August 19, 2020

A Canticle for Leibowitz, a review

This is the world of Walter M. Miller Jr.’s wonderful A Canticle for Leibowitz (1959) which I

recently had the pleasure of re-reading after a span of many years.

A Canticle for

Leibowitz is a fragmented read, consisting of three discrete stories separated

by centuries of time. Each were short stories originally published in The Magazine of Fantasy and Science Fiction.

As a novel this stitched-together structure helps to reinforce one of Miller’s

central messages: The painstaking, fragmentary, and precarious state of knowledge

transmission and preservation.

At its heart Miller’s book is a re-imagining of what the medieval

monks did with classical Greek and Roman literature, transcribing it

laboriously and preserving the flame of past knowledge until it could be used

in a more enlightened age. While historical monks survived barbarian predation

and Viking raids, in Miller’s novel nuclear war and predatory radiation-scarred

scavengers are the equivalent of barbarian invasions circa 476 AD. The

survivors of the nuclear exchange are subject to a brutal period called the

“Simplification,” where mobs of bitter, vengeful survivors attempt to

eliminate any trace of the science that led them down the path to oblivion.

Books and men that dare to read them are burned and destroyed.

This scenario is played out again in A Canticle for Leibowitz, with the monks of Albertian Order of

Leibowitz carefully preserving the old scientific literature, resurrecting an

arc lamp from old electrical blueprints. By the second and third act technology

has again risen from the ashes.

Wednesday, August 12, 2020

Checking in with Tom Barber

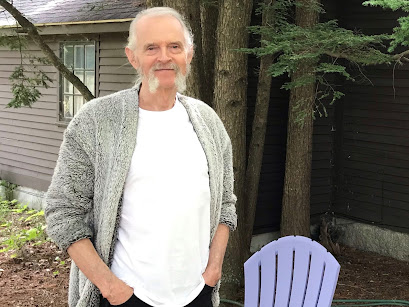

|

| Tom outside his home. |

You can find a couple write-ups of my previous meet-ups with

Tom here:

https://thesilverkey.blogspot.com/2019/08/a-meeting-with-tom-barber-sword-and.html

https://thesilverkey.blogspot.com/2019/09/a-meeting-with-tom-barber-part-2.html

Tom dropped out of painting for a few years while battling alcohol

addiction, but has since returned with a vengeance, getting some steady work

from Bob McLain over at Pulp Hero Press. One of his recent projects was the

cover of Flame and Crimson. I was

incredibly honored to have someone of Tom’s caliber on the book.

Tom is a fun, interesting dude. We talked for a couple hours

about some experiences he had meeting the likes of Harlan Ellison and Andrew J.

Offutt at conventions (Ellison purchased one of Tom’s paintings at WorldCon in

Phoenix), meditation and Zen states and humanity stuck in cycles of violence, checks

bouncing for work he sold to Amazing

Science Fiction, and the tension artists face trying to reconcile

illustrating for money vs. pursuing their true muse. All while outside on his

front lawn, socially distanced of course, and enjoying the sunny 80 degree

weather.

The coolest bit to come out of our meet-up is the news that

Tom is working on a short memoir of his own for Pulp Hero Press, one that will

focus on his addiction years (his “drinking years”) and eventual recovery. The

working title is Artists, Outlaws, and

Old Timers. As befits the author it will be illustrated throughout with

Tom’s own artwork. Tom is still writing the manuscript but is nearing

completion. It will contain some amusing scenes from his early days in the late

1960s attending art school and breaking into commercial work, convention life,

crazy bohemian days in Arizona, and recovery and lessons learned.

|

| Train to Nowhere |

Sunday, August 9, 2020

My Father, The Pornographer: A Memoir

His son, author Chris Offutt, tells his father’s story with

incredible bravery and honesty and a raw, pull no punches style in My Father the Pornographer: A Memoir (2016).

I found this book to be absolutely fascinating and extraordinarily

well-written, and burned through it in a matter of two days.

Andrew J. Offutt was “controlling, pretentious, crude, and

overbearing” and spent most of his hours “in the immense isolation of his

mind,” according to Chris. He demanded dead silence in the house while he

hammered away in his office at this typewriter, churning out content. Chris

often took to the woods to escape a stifling home existence.