|

| They're back! |

"Wonder had gone away, and he had forgotten that all life is only a set of pictures in the brain, among which there is no difference betwixt those born of real things and those born of inward dreamings, and no cause to value the one above the other." --H.P. Lovecraft, The Silver Key

Sunday, August 14, 2022

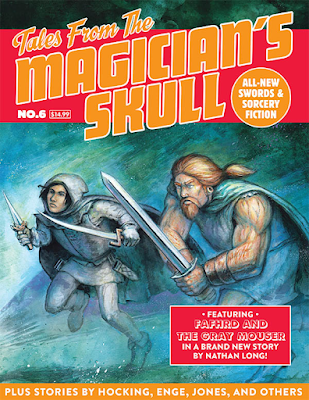

Tales from the Magician’s Skull #6

Friday, August 12, 2022

Thin Lizzy, "Emerald"

With their shields and their swords

To fight the fight they believed to be right

Overthrow the overlords

To the town where there was plenty

They brought plunder, swords and flame

When they left the town was empty

Children would never play again

From their graves I heard the fallen

Above the battle cry

By that bridge near the border

There were many more to die

Then onward over the mountain

And outward towards the sea

They had come to claim the Emerald

Without it they could not leave

Thursday, August 11, 2022

Wednesday, August 10, 2022

Getting political in fantasy fiction

A good idea? Or, should politics be avoided? Can it ever be avoided, when authors are humans and presumably possessed of some political bent, lightly or tightly held?

I think politics can be de-emphasized, and unless you’re setting out to write something like Gulliver’s Travels, think it usually should. Good writers show, not tell, which means showing life in all its richness and complexity, including the non-political sphere (it exists). But shorn of anything remotely considered political your writing runs the risk of being bland. Or becoming the Weird, otherworldly variety of Clark Ashton Smith’s wildest stories.

Getting political cuts both ways. For the liberal who’d like to see something closer to socialism implemented, punching up at corporate overlords through their fiction has understandable appeal. The bad guys can be Jeff Bezos or Elon Musk. But the perceived war on white men, capitalism, and the embrace of identity politics, has brought with it authorial counter-reaction from conservative authors.

Doing this type of work requires sophistication and a deft hand, or else it comes across as crass, activist screed. I don’t like reading painful, on the nose allegory. If you choose to write about the politics of the day, within a few years when the next leader is elected, you will find that your stories have aged, fast. Your clever references to political figures and hot-button issues will be rapidly outdated, obscure. Which is why I generally recommend either avoiding overt political messages, or better yet, focusing on reality—life as it actually exists, in all its forms, across the political spectrum and in the non-political sphere.

J.R.R. Tolkien was influenced by the events of his day, his Catholic upbringing, his World War I experiences (and World War II, despite his disavowal)—in addition to great swathes of non-political input including his deep knowledge of languages and medieval literature. But his stuff resists easy analysis. Is The Lord of the Rings conservative? In some respects, yes. A king is restored to his throne at the end. The Scouring of the Shire brushes up to outright critique of socialism. But the story is also about a multicultural fellowship who put aside their differences to beat a dictator. It reveres environmental preservation, critiquing the rapaciousness and industrial pollutions of Saruman. In other words, it depicts life in its richness and complexity. In so doing it presents glimpses of the truth, not a subjective political message of the day, which is one of the reasons why that work endures.

If you’re a writer, getting overtly political is one way to appeal to an audience, find your tribe, sell books. Certainly there is an appetite for all things political today. But it runs a risk. For example, in an anthology your tribe may discover other authors embrace views antithetical to its beliefs. The crudest example of this is the Flashing Swords #6 incident.

I keep going back to Howard for how to do this the right way (or at least the way I prefer my fiction). Are his Conan stories political? In a broad sense, yes. We can read Conan cutting through corrupt judges and monarchs as rebellion against the established order, a counterreaction to the injustices wrought by the Great Depression. But they are not direct critiques of Herbert Hoover (or maybe they are; if someone makes the case I’ll read that essay). They take a much broader, longer view of the course of human history, offering a dark view about the cyclical rise and fall of civilization and the imperfections in human nature, which makes them far more dangerous and memorable than mere of-the-day political commentary. It’s part of what has made Howard’s stories last. As has their non-political elements, like Howard’s incorporation of the literature of the west, and the Texas landscape.

I also think Leiber is instructive. Leiber’s critique of civilization was more subtle than Howard’s, his view of barbarians less romanticized (see “The Snow Women”). Rime Isle, the heroes’ end, was perhaps his statement on the need to break away from gods and cities, religion and politics. Perhaps old Fritz was on to something here, even though I found most of these latter stories wanting. Which maybe tells you something about our inability to ever flee reality.

I have said that my credo is literary freedom, and I stand by it. If getting overtly political in your fiction is what you want, it’s well within your rights, under the First Amendment. It should be this way.

If you want to write about a hero who rips down a wall built by a dictator, and opens the borders to a suffering neighboring community, you might be meet with cheers (from some). Others will boo your effort. How about a story about a barbarian who hacks his way through crime-plagued inner cities, solving violence with violence? Will you/should you accept that story?

Be prepared for criticism, both of the unfair/ugly variety from readers with axes to grind, but also of the thoughtful kind who see things from a different angle.

Life is lived in the middle. Political theory must meet reality. If you can live with that, have at it.

Saturday, August 6, 2022

More awesome Tom Barber art

Tom Barber was kind enough to send me a few more digital images after my recent visit to his home and studio a couple weeks ago. I'm posting them here with his permission, appended with a few comments.

Enjoy the hell out of them. I sure did. I'm particularly fond of the first. That's talent, folks.

|

| This is Harlequin, the band/friend of Tom's mentioned in my prior post. Not the Harlequin from Canada. Started in Florida and ended up in Boston. |

|

| PTSD. |

|

| Compadre of the skeletal warrior from the cover of Flame and Crimson. |

Friday, August 5, 2022

The Crue, Poison, Def Leppard, Joan Jett

This Metal Friday will actually be a Live Metal Friday. Of the Hair Metal variety.

Tonight I trek into Boston to Fenway Park to see an quadruple bill of aging 80s rock legends: Joan Jett, Def Leppard, Poison, and Motley Crue.

I have seen 3 of these 4 bands separately (never Jett) and each was fun. Nothin' But A Good Time, you might say. But, put them all together and you've got fireworks. You might have to Kickstart My Heart at this show-stopping lineup.

I'll stop there.

As anyone who follows this blog knows I'm much more a fan of what I call (in an admittedly gatekeeping/obnoxious way) real heavy metal, bands like Iron Maiden, Black Sabbath, Judas Priest, etc. But, I do like pop metal/hair metal too. I have to be in the right mood, which is usually Friday or Saturday night with plenty of cheap cold beer.

Both boxes are checked, all systems go. Let me get through today and then I'll be time-traveling back to the 80s. There's a shitload of fun, rocking hits from these bands that regularly make my playlists. Can't wait to hear them again tonight.

For today's song, I'll go with "Same 'Ol Situation (S.O.S)." Always loved this one.

Wednesday, August 3, 2022

Some ruminations on sword-and-sorcery’s slide into Grimdark

Sword-and-sorcery continues to show stirrings, and life. Outlets like Tales from the Magician’s Skull, DMR Books, new projects like Whetstone, New Edge, etc., are publishing new authors and new stories that embrace its old forms and conventions. Obviously the genre ain’t what it used to be circa 1970, but who knows what the future may hold for us aging diehards.

I speculate on some of the reasons why S&S died off in Flame and Crimson (which, by the way, just surpassed 100 ratings on Amazon—thank you to everyone who took the time to rate or review the book, as these help with visibility in some arcane, Amazon protected manner). I won’t rehash them all here, they are available in the book.

What I haven’t written as much about is why Grimdark filled the void, what makes that genre popular with modern readers, and what we might have to learn from this transition.

First, I am of the opinion that Grimdark is the spiritual successor to S&S. One of them, at least. I agree with the main thrust of this article by John Fultz. S&S has many spiritual successors, from heavy metal bands to video games to Dungeons and Dragons. But in terms of literature, the works of Richard Morgan, Joe Abercrombie, and George R.R. Martin, bear some of the hallmarks of S&S, while also being something markedly different.

I believe this occurred as part of a natural evolution within S&S, with some things gained, others lost. As occurs during the general course of all progress.

First, I think this shift mirrored a broader cultural change. If we accept that Grimdark is marked by graphic depictions of violence, as well as a bleak/everyone is shit/might is right outlook (grossly simplified), then we can see what was acceptable in the 1950s-early 70s was different than what we saw in the popular culture in the 1990s and into today. Heavy metal was born in 1970 with the gloom and doom of Black Sabbath, before Judas Priest and Iron Maiden, then Metallica and Megadeth and Slayer, took the form to 11, giving the hard rock of the late 60s/early 70s a much harder, darker, aggressive edge. Popular westerns went from the tough but heroic John Wayne to the spaghettis of Clint Eastwood, reaching a culmination in Unforgiven that essentially deconstructed the genre and cast the “hero” in a very different light. War films gave us Platoon instead of The Longest Day. Frank depictions of sexuality also became acceptable. Essentially “the culture” decided this shift, artists and directors and musicians needed to break norms and explore new territories to keep their visions fresh and original. It’s a natural process, the way art always evolves. But things are lost, old forms abandoned along the way. S&S was a casualty.

I also think the ascendance of Grimdark mirrored a change in publishing trends. Grimdark borrowed from high/epic fantasy in form and length, and with its emphasis on world-building. This aspect is less appealing to me, for the most part (I love Tolkien, but I think very few if any authors have done the world-building aspect of Tolkien as well). But it seems many fantasy readers love getting lost in worlds and so gravitate toward multi-volume series. I won’t argue with that impulse, though I think a really good writer can accomplish that with few words and deft sketches of detail. Trilogies and stretched-out stories offer a far more reliable and lucrative business model for publishers and authors. But less cynically they also allow for greater character development, a thought which struck me during a recent read of Abercrombie’s The Blade Itself (Glokta and Logen Ninefingers and Jezal all feel very real, and three-dimensional, as we consistently read/hear what they are thinking). Again, some like this aspect of fiction, some don’t. S&S can do this, and has, albeit across multiple stories (see Fafhrd and the Gray Mouser), but it’s not a typical hallmark of the subgenre. But readers seem to want that, hence our fascination with origin stories, identification with characters "like us" rather than larger-than-life or abstract heroes, etc.

The general cultural trend of amplified violence and post-Vietnam war-weariness led to grittier literary material like David Gemmell’s Legend and Glen Cook’s The Black Company. Before Martin gave it full life with A Game of Thrones and his multivolume A Song of Ice and Fire, and Joe Abercrombie picked up the torch with The First Law trilogy. And we have what we have today in Grimdark, a sort of mash-up of S&S and epic fantasy and other influences.

Grimdark’s ascendance doesn’t mean we can’t have S&S too, with its greater emphasis on the short form, wonder and weirdness, and less emphasis on world building and cast of characters stories. But whether it will become commercially viable again remains to be seen. Baen is about to give it a shot with its signing of Howard Andrew Jones, and Titan Books set to publish a new Conan novel.