Part three of Blogging The Silmarillion

continues with chapters 6-9 of the Quenta Silmarillion

.

——–

Say farewell to bondage! But say farewell also to ease! Say farewell to the weak! Say farewell to your treasures! More still shall we make. Journey light: but bring with you your swords! For we will go further than Oromë, endure longer than Tulkas: we will never turn back from pursuit. After Morgoth to the ends of the Earth!—from Fëanor’s speech to the Noldor, J.R.R. Tolkien’s The Silmarillion

Difficult and boring. Too dry. Too much history and too many names. Not enough heat and passion.

Difficult and boring. Too dry. Too much history and too many names. Not enough heat and passion. These are some of the typical complaints often leveled at

The Silmarillion. As you can probably guess I don’t have much sympathy for them, and I hope that my first two

Blogging The Silmarillion posts have helped dispel the myth that nothing exciting or worthwhile happens in this book. But after 50 pages of

The Silmarillion it’s not an unfair question to ask (literally and figuratively):

What’s the story, JRRT?

The disappointed and befuddled critics who reviewed

The Silmarillion back in 1977 wanted a main character upon whose sturdy frame the story could be told; at the outset of the book such a protagonist does not seem to exist. Instead of hobbits, we’re fed a steady diet of creation myths and lists of demigods.

But I would counter with: Did these critics and disappointed readers ever get beyond Ainulindalë and Valaquenta? And if they did, how did they miss the great, proud, headstrong, damn the torpedoes Noldorin Elf known as Fëanor? Fëanor is what I would consider the first “big name” in

The Silmarillion, a larger than life hero that seems to have strode out of some wild northern legend and into the pages of Tolkien’s magnificent legendarium. He shatters the pale, washed-out, emotionless Elven stereotype that people have unfairly associated with Tolkien.

In addition to being a kick-ass character, Fëanor introduces a couple important themes that run throughout The Silmarillion: The sin of excessive pride, and the danger of embracing the material at the expense of the spiritual. His character also adds another facet to Tolkien’s interesting and complex portrayal of the nature of evil.

(As an aside, Melkor is also shaping up to be another main characters that critics of The Silmarillion seem to overlook. Unlike Sauron, who we glimpse only as a shadowy dark lord or as a burning eye in The Lord of the Rings, Melkor is firmly on center stage. We see his ambitions and fears, his triumphs, defeats, and pettiness all over the pages of this book).

Fëanor is the eldest son of Finwë, king of the Noldor. His name means Spirit of Fire, and this is quite apt: He burns with the fires of unquenchable passion, and seems more akin to Man than Elf in this regard. His mother, Miriel, dies shortly after delivering Fëanor, so much energy has his coming into the world consumed.

The Noldor are master craftsman and Fëanor represents the pinnacle of their unearthly skill. Drawing on all his abilities he fashions the Silmarils, three gemstones which contain the light of the two trees of Valinor. They are a once in a lifetime creation whose beauty transcends the skill of their creator.

But the Silmarils are of course eyed greedily by Melkor. As I alluded to in my last post, Chapters 6-9 of The Silmarillion have a bit of an Empire Strikes Back feel to them: Evil arises from the ashes of defeat to shatter any illusions of triumph. In these chapters Melkor returns to wreak his revenge, of which Fëanor gets the brunt.

Chapter 6 of The Silmarillion begins with a time of bliss. The light of the two trees is shining on Valinor, and the Valar and Elves are at peace. Melkor, defeated by the Valar in the Battle of the Powers, is in chains. But his time of imprisonment (he got three Ages in the slammer for breaking the lamps of Illuin and Ormal, and causing general mayhem on Arda) is drawing to a close, and he sues for pardon. Most of the Valar want to keep him locked up, but Melkor’s words to Manwë are sweet, and he promises to use his powers in the cause of good. Manwë lets Melkor go and allows him to remain in Valinor.

Manwë has made an apparent grievous mistake. Melkor obviously still hates the Valar and the Elves, in fact more than ever after his imprisonment, and shortly after his release begins planning his revenge. Having learned a lesson that he cannot win by force, Melkor uses his sweet tongue to sow seeds of discord among the Noldor. He appeals to their pride, telling the Noldor that the Valar let them live in Valinor only so that they may keep them under their thumb. He tells them that they could be ruling in splendor on Middle-earth, masters of their own destiny, and not the whim of the Valar.

|

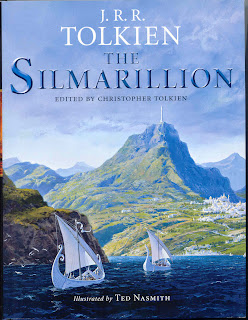

| Ungoliant and the Two Trees, Ted Nasmith. |

In addition to poisoning the minds of the Noldor, Melkor also wreaks more immediate, visible havoc. In Chapter 8 he flees Valinor, returns in secrecy with the great monstrous spider Ungoliant, and poisons and destroys the two trees of Valinor. He then adds insult to injury by slaying Fëanor’s father and stealing the Silmarils.

Fëanor is enraged. He curses Melkor, naming him Morgoth, the Black Foe of the World, and the Elves call him by that name ever after. Fëanor vows revenge, and against the counsel of the Valar leads the main of the Noldor on a mission of vengeance. He commandeers the beautiful swan-ships of the Teleri and slays a great number of the sea-Elves in terrible incident known as the Kinslaying at Alqualondë.

Fëanor’s actions earn him exile from Valinor. The Valar known as Mandos—aka, Fate—pronounces on them the Doom of the Noldor, which is pure poetry from Tolkien:

Tears unnumbered ye shall shed; and the Valar will fence Valinor against you, and shut you out, so that not even the echo of your lamentation shall pass over the mountains.

All in all it’s absolute disaster for the forces of good, and it appears as though it’s all Manwë’s fault. Why couldn’t he have just kept Melkor locked up?

It’s largely a given among Tolkien’s readers that mercy is always the correct path to walk in Middle-earth. Recall Gandalf’s famous quote from The Lord of the Rings, “Pity? It was Pity that stayed [Bilbo’s] hand. Pity, and mercy: not to strike without need.” Indeed, Frodo’s mercy and pity for Gollum saves the Third Age from a long, dark rule under Sauron. But Manwë’s apparent mistake of freeing Melkor makes us re-think this long-held belief.

Of course, we don’t know whether Manwë’s act of benevolence will work out in the long run. Fate has a very long reach in Tolkien’s legendarium, and at this point in The Silmarillion it remains to be seen whether his choice to free Melkor will ultimately work out for good or ill.

—–

Fëanor: An exile of his own making?

As I mentioned at the outset of this post, Fëanor is three-dimensional character. He’s got grand ambitions and a fearless, take-no-prisoners attitude. He’s also riddled with faults, including a swollen pride and an attachment to the work of his own hands. He’s complicated, and damned interesting.

Personally, I find Fëanor’s thirst for vengeance rather sympathetic. When he says:

Here once was light, that the Valar begrudged to Middle-earth, but now dark levels all. Shall we mourn here deedless for ever, a shadow-folk, mist-haunting, dropping vain tears in the thankless sea? Or shall we return to our home?

My reaction is: Go Fëanor. Screw the Valar: Rally the Noldor and go kick some ass. In a book which doesn’t contain an identifiable main character in its first 50-plus pages, he’s a red-blooded hero we can latch onto like a drowning man at sea. I certainly did upon this most recent re-reading.

Though he’s an Elf, Fëanor doesn’t deliberate or take the long view, but chooses to act, and act like a Man. When the herald of Manwë warns Fëanor of the folly of leaving Valinor on his mission of revenge, Fëanor states that he’d rather find ruin in Middle-earth than sit idly by in paradise:

“If Fëanor cannot overthrow Morgoth, at least he delays not to assail him, and sits not idle in grief. And it may be that Eru has set in me a fire greater than thou knowest. Such hurt at the least will I do to the Foe of the Valar that even the mighty in the Ring of Doom shall wonder to hear it.”

In other words: I may perish, but I’m doing some damage on the way down. I like this attitude: It’s got a northern, hopeless, death-wish feeling about it.

But Fëanor is not without faults. He’s selfish and rather vain, particularly when it comes to his own skill as a craftsman. He lacks humility in the face of his betters: When he utters that the Noldor shall become “lords of the unsullied Light, and masters of the bliss and beauty of Arda,” he has stepped over the proverbial line in the sand and crossed into Valar/ Ilúvatar territory.

Fëanor also seems to lack an altruistic bone in his body. He leads his people into exile not out of a desire to save Middle-earth, or to get revenge for his father (though these certainly add fuel to his fire), but because he wants his Silmarils back. When you get to the heart of why the Noldor leave Valinor, it’s over possessions. Contrast this with Galadriel: She also chooses to join the Noldor in exile, but is motivated by her love for Middle-earth. In this respect, she’s closer to Ilúvatar—to the land, his primary creation—and not a lesser Elf-made subcreation. Thus she is in the right, even in choosing exile.

|

| Ted Nasmith - The Kinslaying at Alqualondë |

Later Fëanor goes fey, stranding Fingolfin and some of the Noldor whom he deems unworthy (including Galadriel) on the barren coast of Araman. He burns the stolen swan-ships of the Teleri to prevent his people from returning and helping their brethren, which would potentially slow down his mission of revenge. Fingolfin, Galadriel and the abandoned Noldor respond with a quiet, heroic endurance, eventually reaching Middle-earth (though not without great loss) after a long voyage by foot across grinding ice. In contrast, Fëanor’s brash, brazen, martial quest is not half so noble.

While Tom Shippey explains it far better than I in his seminal work J.R.R. Tolkien: Author of the Century, Tolkien performs a neat trick with his depiction of evil throughout his legendarium: He leaves it up to the reader to decide whether evil is an actual force acting upon us and influencing us, or whether it is of our own making. Shippey calls these two opposing theories Manichaean and Boethian. The Manichaean school holds that evil is a real external force that can influence or overwhelm us, while the Boethian view holds that there is no such thing as evil, that it is an absence, and that “evil” arises out of selfish decisions.

Applying Shippey’s theory to The Silmarillion raises an interesting question: Is Fëanor a victim of Melkor’s Manichaean influence, or a reckless Elf bent on his own destruction? Did he rebel against the Valar and choose exile because of Melkor’s poisonous lies, or did he succumb to his own selfish desire to reclaim the Silmarils, to show up the Valar, and to be a master of his own fate, forsaking the wisdom of the gods?

What do you think? The text seems to support both interpretations, so we can’t be sure, but one thing is certain: Tolkien makes us think in The Silmarillion. This is always a good thing.

Terrific Tolkien: Morgoth dissed

The Lord of the Rings contains a great scene in which Aragorn rides up to the Black Gate and orders Sauron to come out of his dungeons to “have justice done upon him.” It’s an incredibly brave and brazen act, this mortal man issuing marching orders to one of the Maiar.

Yet Aragorn’s act pales alongside the verbal dressing-down Melkor/Morgoth receives in The Silmarillion. No Man or Elf in Tolkien’s legendarium would dare diss a Valar to his face, save one alone: Fëanor.

Here’s the set-up: Shortly after he is freed from his imprisonment in the fastness of Mandos, Melkor comes to Fëanor’s home in Formenos in an attempt to recruit Fëanor to his side. Melkor’s poisonous lies at first find a willing ear: Fëanor’s heart is still bitter from his humiliation at the hands of the Valar, and the smooth words of Melkor, the mightiest of the Valar, seem to promise powerful aid and allegiance.

But when Melkor’s conversation turns to the Silmarils, Fëanor sees through the dark lord’s disguise, and dismisses this greatest of the Valar with a contemptuous send-off that surely echoes throughout fantasy literature:

“Get thee gone from my gate, thou jail-crow of Mandos!” And he shut the doors of his house in the face of the mightiest of all the dwellers in Eä.

Wow … naming Melkor, lord of darkness and the equivalent of Milton’s Satan, a jail-crow of Mandos, and then slamming the door in his face? That takes some serious stones.

|

| Fëanor... fuck around and find out. |