|

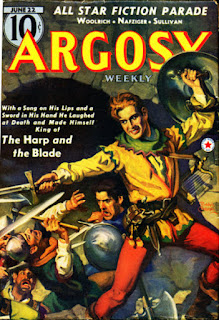

| At 10 cents you get your money's worth |

But, after reading John Myers Myers’ The Harp and the Blade, I would now tell aspiring authors: Here’s a pretty solid template.

This book moves. The Harp and the Blade was originally published as a seven-part serial in the venerable magazine Argosy in 1940, and in paperback still bears some hallmarks of its pulp heritage. It needed to be swift, and grab readers from issue to issue. Each chapter is just 10 pages, and the entirety of the book is a mere 230 pages. No needless descriptions. No navel-gazing “world building” (it is set in 10th century Dark Ages France, on the cusp of the feudal era, so not a whole lot of that is needed). More to the point: Something important happens each chapter to advance the plot.

|

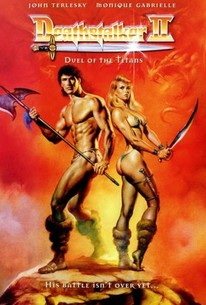

| S&S beefcake... 1985 style. |

Now, is The Harp and the Blade sword-and-sorcery? Maybe, but probably not. It’s best classified as historical fiction. Although you could be forgiven for thinking it was S&S, so closely does it skirt that territory. Certainly it’s packaged that way. I have the 1985 edition as published by Ace. Look at that cover! Two overmuscled dudes, one a hip bard with 80s surfer hair, the other a classic Boris Vallejo style barbarian. This was definitely marketed to the same audience that devoured the Lancer Conans in the 60s and the DAW Elrics in the 70s. Publishers of the era were going to great lengths to ride the sword-and-sorcery wave, although by the mid-80s the subgenre was about to disappear from the shelves, almost overnight, with few exceptions (Keith Taylor’s Bard novels, for example). Morgan Holmes calls this “The great sword-and-sorcery extinction event.”

Oh, and the “barbarian’s” name happens to be… Conan! Not the Conan you’re thinking of, and in fact other than being a resourceful, charismatic leader with some skill with a blade, bears no resemblance to Robert E. Howard’s most famous creation. The name Conan has historical Gaelic/Celtic roots, although one might assume Myers Myers was at least familiar with Howard’s work.

Packaging alone is not enough, but what edges this book back into S&S territory is the geas our hero, the bard Finnian, is placed under. After callously watching a man get murdered in a tavern brawl when he

may have intervened and saved a life, Finnian is shamed (and possibly,

ensorcelled) by a druid in a wonderful scene atop a cromlech on a

moonlit night. Thereafter his life is changed; he begins to accept

responsibility, and act out of a sense of altruism. "From now on, as long as you stay in my land," here he swept an arm to include all directions," you will aid any man or woman in need of help," the old man declares. This is skillfully handled by Myers Myers, and it may just be shame, or the power of persuasion, that causes our hero to begin to take responsibility. But it may be magic.

This is the heart of the book, and the message that lies beneath the page-turning action. Finnian is, like many of the classic heroes of S&S, an outsider. He is literally that—an Irish bard in foreign lands, making his living with his songs and his poetry, never settling down but moving from modest payday to payday. Just living, untrammeled. Lacking any commitments, he has nothing to tie him down, but seemingly nothing to give his life meaning, either. He’s at a crossroads.

Make no mistake, this is THE struggle all men face. Do we drift through life, viewing others’ misfortunes as not our own (“not my circus, not my monkeys”—not a fan of that phrase), dreaming, noncommittal, childlike? Or, do we take a stand, find principles we can live by, put down roots, raise a family, and get to work on adulthood? Personally, I don’t think there is a choice, and if you fail to grow up it will bite you in the end, hard. Peter Pan is a cautionary tale, not an ideal, and the lost boys are just that.

The book has an interesting, muted ending, where all does not turn out like we had thought, or hoped, or expected (and, which I had guessed due to some mild telegraphing from Myers Myers). I won’t spoil it here.

Despite what I’ve written above this is not a heavy book laden with psychoanalysis. It’s action-packed, with death defying rescues and escapes, violent combat, romance, wine, and song, set against a dangerous backdrop of lawless lands where outlaw bands carve out fiefdoms at the point of a sword, as Danes plunder from the North and Moslems threaten incursion from the South. There is drama, but it’s gritty, grounded, and the world does not hang in the balance. Just enough characterization to allow us to latch on to the main character. In short, good stuff.

Sadly Myers Myers seems to have fallen into obscurity, but for a time had gained a level of popularity and critical respectability with Silverlock (1949), which I have not read. I can recommend The Harp and the Blade, however. Even if not S&S it follows the formula us fans want and appreciate.