Where do new sword-and-sorcery authors go to test their mettle in the arena, seeking glory (or at least, companionship with fellow brothers and sisters-in-arms)? And where might you find the occasional veteran belly up to the bar, with a rousing tale to add to the cacophony of combat?

Why, in the pages of Whetstone, the amateur journal of sword-and-sorcery.

I just finished reading Whetstone #5 and wanted to share a few impressions.

First of all, look at the cover of this thing. This is as close to perfect as it gets. While you could say it leaves you with the wrong impression—Whetstone is not an OSR gaming publication—it conveys what the contents are all about—nostalgia for an old(er) subgenre of fantasy, given new life with new interpretations and new voices.

Editor Jason Ray Carney’s intro is worth reading. So many of us have spent much digital ink, arguably too much, trying to find some precise definition for sword-and-sorcery. At times it gets tedious--this coming from a guy who wrote a complete non-fiction treatment (as Arnold said in Conan the Destroyer, “Enough Talk!”)

Carney boils down S&S to a general feeling rather than specific tropes. This is as good as lens as any when analyzing the genre. Carney instead focuses on why we like S&S, which he identifies as its depiction of conflict, often against an amorphous threat that is simultaneously tangible and supernatural, and possibly representational or symbolic:

What do we feel when we imagine a brutalized sword and sorcery writer laughing at the stars? What do we feel when we read about a mere mortal--an ephemeral form--violently confronting eternity, the cosmos, the infinite in all its eternal strangeness? Why are sword and sorcery writers obsessively drawn to their primary theme: the unresolved antagonism between the natural and the supernatural? The profane and the sacred? The individual and the cosmos?

On to the contents.

Reviewing collections of short stories by multiple authors is tricky. Attempting to review 20 stories one-by-one is folly, not something I have the time to do, and the result would be brief unhelpful encapsulations. The stories are all very short, as the submission guidelines call for stories between 1500-2500 words, no more no less. So even if they are not to your taste, they pass quickly.

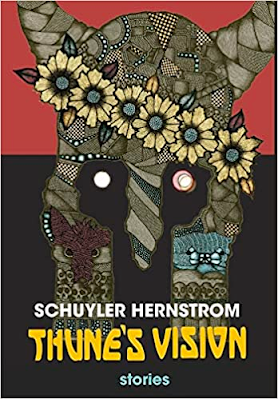

This is an amateur magazine so don’t go into it expecting to read peak Robert E. Howard, Clark Ashton Smith, Manly Wade Wellman, or even some of the better modern authors like Schuyler Hernstrom. A couple of the writers have recognized names and bodies of work, but most are cutting their teeth. As a whole, almost all the stories were entertaining (some were deliberate and welcomed tongue-in-cheek, for example the charming yet gory “The Riddle of Spice”). I detected some obvious Conan the Barbarian (film) influence, Howard, Smith, and Fritz Leiber and Michael Moorcock notes and influences in many of the stories. Gladiatorial pits feature prominently, as do stories of vengeance. Some stories feel like unfinished parts of a bigger story, interludes or chapters. There are some recurring heroes from previous issues of Whetstone, old champions making their returns to the ring.

Naturally I liked some more than others and wanted to call out a few highlights.

I enjoyed T.A. Markitan’s “Just Desserts,” specifically for the tone it strikes, and its inventiveness: A warrior accompanied by a playful ghost, and a village with dark secrets. It’s well-conceived, and well-executed, a cascade of weird elements in a tightly-plotted little gem of a story with a fun reveal at the end.

Gregory D. Mele’s “Salt Tears” deftly sketches an island culture and customs and tells a compelling little story of muted heroism and regret. He does a fine job making a foil, Bembe, both a bastard and somewhat sympathetic. It also comes to a satisfying, thoughtful conclusion. Well done stuff.

Chuck Clark’s “Doors” leaves you wanting more of his recurring character Turkael, who is a hero but with a mysterious past, one of a group of faceless men with crystal bones and uncanny swords. It feels like you’ve been dropped into a larger story, both for better and for worse, but more of this character is revealed in previous issues and I expect future installments of his story will be coming.

Nathaniel Webb’s “The Smoke Ship” has possibly the best depiction of battle in the issue (the last story in the collection might have it beat), a weird and ghostly sea battle that feels desperate and real, and a nice blend of the historical and mysterious.

I really enjoyed Cora Buhlert’s “Village of the Unavenged Dead.” It reads like Clark Ashton Smith but without the baroque language. There is a detached air to the writing, almost a fairytale feel, yet it's a fast-moving story of revenge with sympathetic protagonist and a satisfying resolution. The story could have gone ultra-dark but Buhlert reins it in nicely.

Whetstone #5 concludes with a tale by polished veteran of the craft, Scott Oden’s “At the Gate of Bone.” This story reminded me very much of David Gemmell or Steven Pressfield, a grizzled warrior relaying an old tale of a valiant but doomed last stand against an overwhelming horde. Orcs and badass horn-helmed warlords and spilled viscera. Really good stuff if you like that sort of thing.