According to Michael Moorcock, J.R.R. Tolkien’s The Lord of the Rings has endured solely because it’s comfort food. So proclaimeth the author of the Elric stories in his seminal essay

“Epic Pooh".

Well, I’m here to knock a little stuffing out of his puffed-up essay.

“Epic Pooh” criticizes The Lord of the Rings on the weakness of its prose style. It also attacks Tolkien’s underlying themes and ideas. It accuses him of failing to challenge the reader and offering artificial happy endings instead. According to Moorcock Tolkien is guilty of glorifying warfare, of failing to question authority, and for ignoring the problem of death. He makes other spirited attacks of the work (and the author) as well.[*]

The first argument is highly subjective, a matter of taste for which I have little argument. Moorcock is entitled to dislike Tolkien’s prose, and if he finds it too coddling, removed, or just plain sub-par, that’s fine. I happen to enjoy it very much, but different strokes for different folks and all that.

But once you get past its criticisms of style, “Epic Pooh” fails rather epically as a critique of Tolkien’s themes. Let me explain.

Moorcock takes Tolkien to task for many perceived crimes in “Epic Pooh,” but perhaps most of all for using The Lord of the Rings to tell “comforting lies” and coddle the reader. Says Moorcock:

There is no happy ending to the Romance of Robin Hood, however, whereas Tolkien, going against the grain of his subject matter, forces one on us – as a matter of policy.I’ve heard this argument made elsewhere and always found it to be a gross misreading of Tolkien’s work. Presumably because The Lord of the Rings ends with the defeat of Sauron, and the restoration of order, it is therefore a simplistic, neat, bow-tied conclusion in which our heroes return home happy and whole, safe and sound.

On the contrary, I would argue that the victory over Sauron is only a temporary reprieve against the encroaching dark. This is the great sadness of The Lord of the Rings—there is home and hearth for some of the victors, but not all of them, and perhaps not even for most. When Frodo departs for the West it’s on a full ship: Gandalf, and Elrond, and Galadriel, and the main of Middle-Earth’s elves are sailing away, too. Magic has left the world. The great evil of the Third Age is defeated, but its void will be filled with other, more banal but equally sinister incarnations of evil. In the wake of the likes of the elves and of Gandalf (and even Saruman and the Balrog and the orcs) comes the vagaries of men, and with them their propensity for both great good and unspeakable evil.

Wounded soldiers return with traumas seen and unseen, and this is evident in Frodo, who bears wounds that are deep indeed. Some essential part of him has been left on a foreign field, and his wounds are too grave to allow him to enjoy the peace he has so dearly bought:

I tried to save the Shire, and it has been saved, but not for me. It must often be so, Sam, when things are in danger: some one has to give them up, lose them, so that others may keep them.In summary, The Lord of the Rings has a complex, bittersweet, melancholy ending. Happy it is not.

Moorcock also derides Tolkien for contributing to the glorification of war and the death of young soldiers:

It was best-selling novelists, like Warwick Deeping (Sorrell and Son), who, after the First World War, adapted the sentimental myths (particularly the myth of Sacrifice) which had made war bearable (and helped ensure that we should be able to bear further wars), providing us with the wretched ethic of passive “decency” and self-sacrifice, by means of which we British were able to console ourselves in our moral apathy (even Buchan paused in his anti-Semitic diatribes to provide a few of these). Moderation was the rule and it is moderation which ruins Tolkien’s fantasy and causes it to fail as a genuine romance, let alone an epic.This statement is also inaccurate. Nowhere does Tolkien claim that war is a good thing. Rather, the implication in The Lord of the Rings and elsewhere in Tolkien’s writings is that it is, at times, necessary. Lest we forget, Tolkien served in the trenches in the Somme, one of the bloodiest battles of the First World War. He saw unspeakable carnage and death. But he also witnessed heroism of the highest order.

As I stated elsewhere in a

review of John Garth’s Tolkien and The Great War, unlike many of the famous WWI combat veterans whose experience resulted in poems and stories of disillusionment and disenchantment (Wilfred Owen’s “Anthem for Doomed Youth,” Ernest Hemingway’s A Farewell to Arms), Tolkien refused to believe that the sacrifice of brave young men was a waste. Says Garth: “In contrast, Tolkien’s protagonists are heroes not because of their successes, which are often limited, but because of their courage and tenacity in trying. By implication, worth cannot be measured by results alone, but is intrinsic.” This is Frodo’s lot: Thrust into a larger war beyond his control, his selfless heroism in carrying the ring to Mount Doom is but a tiny, insignificant role in the great sweep of combat at Minas Tirith and elsewhere. But it mirrors the great acts of unrecorded bravery on the battlefields of World War I.

The sacrifice of Frodo and Sam is not sentimentalizing, it is Tolkien expressing an honest respect and admiration for the soldiers who suffered through horrific, unbearable circumstances. Tolkien said that the character of Sam was inspired by the British rank-and-file soldiers who served and fought and often gave their lives without fanfare in the blood-filled trenches of World War I, expecting nothing and possessing only the hope of home at the end of it all. Said Tolkien, “My ‘Sam Gamgee’ is indeed a reflexion of the English soldier, of the privates and batmen I knew in the 1914 war, and recognized as so far superior to myself.”

Moorcock states that the hobbits represent a “petit bourgeoisie, the honest artisans and peasants, as the bulwark against Chaos. These people are always sentimentalized in such fiction because traditionally, they are always the last to complain about any deficiencies in the social status quo.”

I would counter with: What is so sentimental and consolatory about Sam’s endurance and will to go on, hoping only to return to home and hearth? I suspect that Moorcock has a problem with the social organization of the Shire to which the hobbits return, not necessarily their bravery in defending it.

Here’s another misguided Moorcock-ianism from “Epic Pooh”:

I don’t think these books are ‘fascist’, but they certainly don’t exactly argue with the 18th century enlightened Toryism with which the English comfort themselves so frequently in these upsetting times. They don’t ask any questions of white men in grey clothing who somehow have a handle on what’s best for us.This statement makes you wonder whether Moorcock missed the scene from LOTR in which Sam looks upon the slain Southron and questions the very nature of war, including its participants and causes, laying it bare in all its futility. From The Two Towers:

It was Sam’s first battle of Men against Men, and he did not like it much. He was glad that he could not see the dead face. He wondered what the man’s name was and where he came from; and if he was really evil at heart, or what lies or threats had led him on the long march from his home; and if he would not really rather have stayed there in peace.Tolkien believed that war is terrible and of last resort, and slain foes are, in the end, just men–and therefore to be pitied. War is necessary when “destroyers” like Sauron or Hitler would impose their will on the free peoples of the world, but it is a duty to be carried out, not glorified. In his famous forward to The Lord of the Rings, Tolkien wrote:

One has indeed personally to come under the shadow of war to feel fully its oppression; but as the years go by it seems now often forgotten that to be caught in youth by 1914 was no less hideous an experience than to be involved in 1939 and the following years. By 1918 all but one of my close friends were dead.Here’s another telling quote (from Faramir, again from The Two Towers) that tells you all you need to know about Tolkien’s views on war:

War must be, while we defend our lives against a destroyer who would devour all; but I do not love the bright sword for its sharpness, nor the arrow for its swiftness, nor the warrior for his glory. I love only that which they defend.Moorcock also attacks The Lord of the Rings for fostering an attitude of selfish self-protection and insularity:

The little hills and woods of that Surrey of the mind, the Shire, are “safe”, but the wild landscapes everywhere beyond the Shire are “dangerous”. Experience of life itself is dangerous. The Lord of the Rings is a pernicious confirmation of the values of a declining nation with a morally bankrupt class whose cowardly self-protection is primarily responsible for the problems England answered with the ruthless logic of Thatcherism. Humanity was derided and marginalised. Sentimentality became the acceptable subsitute. So few people seem to be able to tell the difference.While the woods beyond the Shire are certainly wild and dangerous, Moorcock’s statement is far too simplistic. Experience of life (i.e., that encountered beyond the borders of the Shire) can be dangerous, and often is, but as Tolkien demonstrates, it’s more dangerous to engage in isolationism, to stick one’s head in the sand and do nothing. War is coming to the Shire, and the hobbits must venture beyond its borders to save it. Self-protection and complacency is not a viable option. I note that Sam, Merry, and Pippin return as stronger hobbits, enriched from their experience. Is this experience dangerous? Yes. Is it necessary, and in the end, a good thing? Yes.

Yet the above statements are not Moorcock’s most egregious misreading of The Lord of the Rings. I reserve that for the following:

The great epics dignified death, but they did not ignore it, and it is one of the reasons why they are superior to the artificial romances of which Lord of the Rings is merely one of the most recent.This statement completely falls apart when viewed against the entirety of Tolkien’s works, which confront the problem of death head-on. Take The Children of Hurin, for example, which is an expansion of a story Moorcock would have read in The Silmarillion.[

*]Here Morgoth is a dark demi-god, and a symbol of all that is twisted in mankind’s soul, all that of which we despair in the dark of night, rolled into a being of unspeakable malice. When he lays his curse upon Hurin and Turin, they are truly doomed. Morgoth evokes the ultimate fear of all mankind: that death is the end, and that nothing—literal, uppercase Nothing—awaits us in the grave. Says Hurin:

“Beyond the Circles of the World you shall not pursue those who refuse you."

“Beyond the Circles of the World I will not pursue them,” said Morgoth. “For beyond the Circles of the World there is Nothing. But within them they shall not escape me, until they enter into Nothing.”The Children of Hurin begins and ends with death. The Silmarillion contains far more darkness than light, and carnage (and much defeat for the forces of good) on the scale of some of the worst battlefields of World War I. Even The Hobbit, begun as a children’s tale (though morphed in the writing to something quite different), touches on mortality: Following his epic journey and the costly Battle of Five Armies, Bilbo emerges a very different character, far less insulated and more appreciative of the fragile peace of the Shire, with “eyes that fire and sword have seen, and horror in the halls of stone.”

And as for The Lord of the Rings, its entirety can be viewed a metaphor for death. Where do you think the gray ship bore Frodo? He was dying, man.

In short, Tolkien’s works actively grapple with the terrible reality and uncertainty of our mortality. Demonstrably, they do not ignore it.

In fairness, I do agree with some of “Epic Pooh’s” points. Moorcock laments the ignorance of the reading public when it comes to writers like Fritz Leiber, who are often overlooked in favor of lesser fantasy authors that have achieved more popularity simply because they’re an easy, safe read (agreed). I also think that second-rate Tolkien clones—many of which I enjoyed as a youth—have muddied the waters of fantasy literature and contributed to dragging the genre down in the eyes of critics. However, I don’t think they should be actively avoided as Moorcock suggests, just recognized as derivative.

It’s undeniable that Tolkien was nostalgic. He hated seeing the English countryside disappear, to be replaced by factories and fabricated housing. The polluting mill that appears in “The Scouring of the Shire” was based off of an incident that occurred during Tolkien’s lifetime.

In “Epic Pooh,” Moorcock chides Tolkien for not being able to take pleasure from the realities of urban industrial life. But can you blame Tolkien for feeling embittered at the dwindling of the rural countryside? I cannot.

In conclusion, I’ve returned to The Lord of the Rings time and time again over my lifetime. I enjoy slipping into Middle Earth and meeting up with characters that now feel like old friends. I do take comfort in these aspects of the work.

But each time I do, additional unique and challenging facets of this one of a kind work are revealed. It gets better as I grow older, which tells of its surprising depth and multitude of meanings. The Lord of the Rings is not a comforting lie, but a living, breathing book that changes with each re-reading. The more one reads of Tolkien’s legendarium in The Silmarillion, The Children of Hurin, and The History of Middle Earth, the more suffused in darkness and uncertainty works like The Lord of the Rings (and even The Hobbit) become.

So Mr. Moorcock, pardon me while I return to the table for another helping of this one of a kind “comfort” food, prepared by the finest chef ever produced by the culinary arts school of fantasy fiction. You can take “Epic Pooh” and stuff it.

——

[

*]

*A third strand of Moorcock’s dislike for Tolkien also emerges in “Epic Pooh,” that being his antipathy for Tolkien’s Toryism and conservatism. Moorcock takes Tolkien and C.S. Lewis to task for their politics and, to a lesser degree, their religion. It’s noteworthy that Moorcock in a post-publication author’s note lavishes praise on Phillip Pullman, a lesser literary light than Tolkien by any measurable standard, but a writer whose politics fall into lockstep with his own. But while I suspect that political disagreement is the true genesis of “Epic Pooh,” I’d prefer to leave this debate out of The Cimmerian.[

*]

* I was prepared to cut Moorcock some slack on the basis that he may not have read The Silmarillion before writing “Epic Pooh.” Puzzlingly, Moorcock has read it, and actually cites it in the essay. Therefore, I feel perfectly justified in using it and The Children of Hurin in Tolkien’s defense.

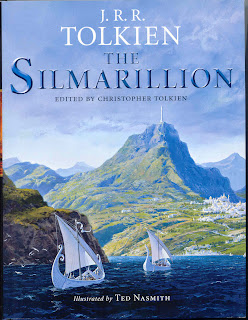

–Artwork by Ted Nasmith

Part nine of Blogging The Silmarillion concludes with Of the Rings of Power and the Third Age

Part nine of Blogging The Silmarillion concludes with Of the Rings of Power and the Third Age