"Wonder had gone away, and he had forgotten that all life is only a set of pictures in the brain, among which there is no difference betwixt those born of real things and those born of inward dreamings, and no cause to value the one above the other." --H.P. Lovecraft, The Silver Key

Wednesday, February 5, 2025

An interesting personal insight into Moorcock’s inspirations

Monday, February 3, 2025

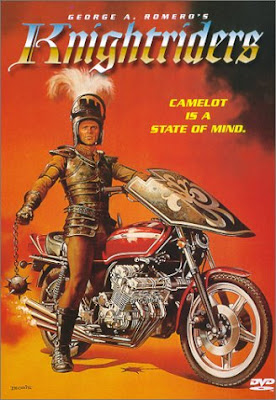

Knightriders, a review

(Warning: Spoilers)

Utopias cannot survive contact with the world of commerce. It’s a message delivered in brutal fashion in the catastrophic ending of George Romero’s Knightriders (1981). Idealism meets the hurtling steel of a freight truck, alternative counterculture going under the wheels of the unstoppable economic engine of the 1980s.

The outcome is predictable and sad. But the leadup and the message of the film is magic.

Weird and flawed, too on the nose perhaps with heavy-handed messaging, Knightriders nevertheless succeeds. It’s unpredictable, meaningful, wonderfully anti-establishment, and utterly singular.

The film opens with a knight (Ed Harris) waking up in a forest, naked and in the arms of his paramour. He kneels and prays over the hilt of his sword, enters a nearby pool to bathe … and proceeds to beat his back with a branch in what we can only presume to be some sort of purification ritual.

Right then you know you’re in for an offbeat movie. And if you had any doubts Knightriders goes straight off the deep end when instead of a horse Harris climbs on a motorcycle and rides back to “Camelot.”

Romero apparently got the idea for Knightriders from the violent medieval reenactments hosted by the Society of Creative Anachronism (SCA). He had planned on horses but producer Sam Arkoff told him to put his knights on motorbikes. The rest is history. Despite the obvious anachronisms it makes painstaking efforts toward medieval realism, from the forging of weapons, romance, and chivalric oaths sworn in fealty to a king, who is really only a man (and a flawed one at that) full of grand ideas and a vision of something better.

Knightriders engages with the myth of King Arthur in a very unique way, demonstrating the extreme malleability of the old stories. It skips the “historical” Arthur of the 5th/6th century and the romantic late medieval-ish setting of Excalibur and instead leaps straight into 1980. There are no knights, no nobles, no real king. The story instead follows a troupe of traveling entertainers who put on a combination renaissance fair and tournament, complete with jousting and full-on melee conducted by knights riding motorcycles. At its head is Billy (Harris), a stand-in for Arthur. He is the heart of this comic but earnest ragtag group of misfits.

Instead of Camelot Billy’s “kingdom” is a commune of outsiders, all wanting something different than the 20th century has to offer. It’s got some similarities with the hippie communes of the 60s, perhaps the last gasp on the verge of the decade of excess.

It wasn’t at all what I was expecting. I of course know Romero from Night of the Living Dead and its various sequels, and so I thought I might be getting ultraviolence, apocalypse, bloodshed. Knightriders is none of the above. There’s plenty of action, of course (the stunts are fantastic and I winced at a couple of the crashes--stuntmen hit the ground HARD. These guys were not making an easy paycheck). But its basically a character drama spread across a large troupe of actors. All of Romero’s old cronies are in the film … as I was watching every five minutes I was like, “wait, there’s the guy from Dawn of the Dead, and another guy from Dawn of the Dead. That’s the guy from Day of the Dead! Wait is that a Stephen King cameo?” (answer—yes.) Tom Savini plays a major role, not a villain but a foil to the king, and who knew—Savini can act. It’s got an interesting Merlin too, a dude with some medical training but equal parts witch doctor, harmonica playing savant, and prognosticator.

It’s amazing Knightriders ever got made, and unsurprisingly it was a commercial flop. Harris admits in a relatively recent interview that while he remains a fan he knew it was destined for obscurity. It’s too odd and offbeat, non-genre, and the intended audience is unclear. Truth be told it’s also flawed. Some of the acting is, to be charitable, pedestrian. The dialogue in many places is stilted. It’s at least 30-40 minutes too long and badly in need of an edit. It meanders and threatens to lose the thread of story.

But I can deal with these imperfections, even its deep and abiding flaws, for what we did get. Imperfection is the way of the world. The courage of knights wavers, their honor and fealty are tested by fortune and fame and lust, and often fail. This film does not fail, and for what it lacks in technical artistry it succeeds through heart. I can think of very few films as earnest and sincere. Romero set out to make a statement about the pressures to sell out vs. staying true to your art, and of the extraordinary difficulties of leading a principled life. Of living a values-led life, to whatever end.

I felt a deep stir of emotion near the end of the film when Harris/Billy/Arthur sees himself not on a bike, but a horse, galloping off on some quest through green lands in a better place. He passes on his legacy in the form of a sword, handing it to a wide-eyed young fan who wanted only an autograph but got much more.

Even if we cannot ever experience earthly utopia the elusive search continues. As long as nonconformists and artists and the disaffected yearn for something more, Camelot beckons.

Saturday, January 25, 2025

Stoner by John Williams, a review

Friday, January 24, 2025

Branching out in my reading, and reaching a crossroads

|

| Squint, and it's Conan? |

Although I prefer fantasy I’m not someone who thumbs my nose at literary fiction (though I wish that worked the other way). As an English major I was exposed to wide range of authors, and loved almost everything I read, from Greek tragedies and Homer to Romantic and Victorian poetry to Hemingway and the modernists. I will pick up contemporary literary/realist works if I find the subject matter sufficiently interesting.

What interests me most is good writing. Genre is not unimportant, but is secondary. A decade or two ago I was reading every S&S title I could get my hands on, but at present moment I’d rather read a well-written novel than mediocre S&S, or yet another generic epic fantasy series.

Tangible example: I’m currently reading and nearly finished with John Williams’ Stoner. I picked this up following a booktube recommendation and frankly I’m blown away by how good it is. It’s a quiet character study, and yet the emotion and intensity—all within the breast of the protagonist—are equal to epic fantasy. Stoner’s created fictional world of college professordom, if not as original as Barsoom, is just as carefully constructed. The (petty) evils of Stoner’s jealous, flawed, and self-centered wife are as wicked and greedy as Sauron. It is full of wonders of a different and more ordinary but no less potent sort.

But my broad reading palette leaves me in a bit of a bind here.

On the one hand, this is my own damn blog, and can write about whatever I want. It’s unmonetized, I have no obligations to fulfill. If you don’t like the subject matter of a given post, it’s easy to skip it.

On the other hand, visitors and readers have a reasonable expectation of discussion of speculative fiction and other fantastic content (I include heavy metal under this broad tent). If I started for example writing about the NFL here it would get downright weird on a blog named after an HP Lovecraft short story.

Do I review Stoner here? Or John Gardner’s On Moral Fiction? I don’t know. I don’t really want to start a new blog—I don’t have the energy and I suspect it would be infrequently updated. But that might be a better option.

Is this question even worth asking? Eh. Probably not. Nevertheless I welcome your opinions, and beer recommendations.

Sunday, January 19, 2025

Blogging the Silmarillion--all parts linked

Friday, January 17, 2025

Rest in peace, Howard Andrew Jones

Make no mistake, this is a first order tragedy. Howard was not old—56 is the middle of a writer’s career, an age where most are still working and at the height of their powers. He was in the midst of a popular series of books published by Baen, the Hanuvar chronicles, one that will probably be remembered as his best work.

More than his professional life, Howard had a vibrant, loving family around him that are suffering an unimaginable loss. And it’s all over.

Howard’s death is a catastrophe. Depressing, and a grim reminder of our own frailty and mortality.

Sad and terrible.

Others knew Howard far, far better than I did, and you can find those tributes elsewhere. Joseph Goodman at Goodman Games, a close friend and collaborator on Tales from the Magician’s Skull, wrote a nice piece. I also found a fantastic and moving tribute on Facebook by author Greg Mele.

Read those pieces, they are from people who knew Howard at a personal level I never did.

I enjoyed Howard’s fiction. My favorite was probably The Desert of Souls. But I think one of his greatest accomplishments were his wealth of posts and essays on S&S, Robert E. Howard, and of course, Harold Lamb. I credit Howard fully for introducing me to Lamb. I’ve got a couple of his Bison Books edited volumes on my bookshelves. A great recommendation, thank you Howard.

As noted previously I served on at least one virtual panel with HAJ, and a podcast. We messaged each other publicly on forums and occasionally privately. He had some nice things to say about Flame and Crimson. I can confirm he was a wonderful human being, friendly and encouraging, non-confrontational and supportive, broad-minded and beneficent. Traits which are increasingly rare these days.

I’ll miss him, and the S&S community will miss him.

I hope one of the enterprising S&S publishers starts an annual award in Howard’s name. Or keeps his wonderful Skull mascot alive, or The Day of Might going, in his honor.

There was something of Hanuvar in him, and so his spirit will live on, eternally, in his works.

Wednesday, January 15, 2025

Gone to the Wolves by John Wray, a review

|

| 80s metal... take me back. |

These days metal claims a larger portion of my mind. In part because, as readers of this blog know, I’m writing a memoir about growing up in the context of this unique genre of music. But also because I just finished a wonderful work of fiction on the subject—John Wray’s Gone to the Wolves.

I’ve read a fair number of works of heavy metal non-fiction, including history (Sound of the Beast, Ian Christe, others) sociological studies (Heavy Metal: The Music And Its Culture, Deena Weinstein), and autobiographies (too many to count). But I can’t say I’ve encountered a work of literary fiction in which heavy metal plays such a starring role.

Gone to the Wolves begins in Florida in the late 80s, a region and a point in time that saw an underground surge of death metal, the emergence of bands like Cannibal Corpse and Death. It shifts the action to the LA Strip and glam/hair metal, before finishing with a third and final act in Norway, home of black metal. We get the time, the culture, and the place of these three culturally and geographically diverse areas, all done well.

And we get the music. There is a lot to like here. Wray is a very good writer, but has a unique talent for capturing sound and the emotion it engenders in its subjects. Reading the book feels like going to a concert, and at times casts a potent spell.

But, more than music Gone to the Wolves is really about the unique friendship shared by its three main characters. The protagonist is Kip, a teen who leaves an out of state broken home to move in with his grandmother in Venice, FL. There he befriends Leslie, a gay, black, nerdy teenager with a big brain for metal. The two later meet Kira, a wild, untamed thrill seeker and Kip’s love interest. The characters don’t speak like any teenagers I know, or knew of; they are too articulate, too smart, too informed. But it works in a dramatized novel.

The dynamics are fun, the characters work, and the story pulls you in. The trio fall into the underground of Florida death metal, graduate high school and leave for L.A. and the crazy party scene on the strip. When that begins to spin out of control and Kira loses patience with its falsity, she ultimately ends up in Norway in the early 1990s. Which as anyone who knows heavy metal’s history was home to some crazy shit—church burnings, an attempted overthrow of a Christian nation, and the revival of the pagan gods of the old north.

I love the details and the commentary of the time. A character named Jackie launches into a soliloquy about the division in metal, one side Dionysian ecstasy and the other set the chaos of Set, as played out in chick friendly hair metal vs. the heavy, real shit, thrash and death metal. It struck me as true. As did the early scenes of hanging out in the middle of nowhere, crowded around a fire with friends, drinking and living for today. I had similar experiences.

I also identified with Wray's portrayal of metal fans as the outsider, apart from the conversations about popular music and fashion-seeking, but instead embracing loud and commercially unfriendly bands, adopting their fashion and making it and the metal lifestyle, well, everything.

I recognize these kids.

But I did have some issues with the book, and a look at Goodreads indicates that others had similar.

It feels like too much is crammed between its covers, in particular the third and final act which morphs into a dark crime thriller. Its tonally different and a bit jarring after the character studies and bildungsroman of parts 1 and 2.

Kira is suffering from deep trauma that is not given adequate treatment, leaving her feeling a bit like an archetype rather than a believable character. And yet, Kira is possessed of something I recognize—the need for authenticity, to move beyond the falsity that papers over so much of life. This was a big part of metal subculture, the battle of true vs. false metal, as sung in explicit fashion by the likes of Manowar. Wimps and posers, leave the hall.

Metal bands fall along on a spectrum, from the tongue-in-cheek “evil” antics of Ozzy Osbourne to actual death worshipping bands like Mayhem and Burzum. So if you’re a metal fan you know which direction the book is heading—toward Norway, drawn by Kira’s authenticity seeking. Wray seeks to explore metal’s darkest recesses but it requires a bit of a stretch to get the action there. Overall I enjoyed the first 2/3 of the book a lot more, which felt true, and the latter section something of the false. But I get why Wray went went there.

I’ve got my limits and black metal is a bridge too far; some of it has atmosphere I can appreciate but it’s too one note/wall of sound for me, as well as genuinely disturbing, even enervating. I made it to Slayer and Sepultura and that was far enough. Metal has dark corners I don’t need to explore and the characters in the book come to feel the same: “This isn’t where I thought my love of rock ‘n’ roll was going to take me,” Kip says at one point, as they pursue Kira’s trail into the heart of Norway, toward a possible rendezvous with death.

Metal remains an untapped source of literary expression, and with Gen-X in the ascendancy and the Boomers and the Beatles mercifully in the rear-view mirror it’s time to reflect on what it all meant. Wray’s novel is a welcome addition to the conversation.

Monday, January 13, 2025

Celebrating Rob Zombie, graphic artist, at sixty

|

| Master of many arts, including graphic. |

Tuesday, January 7, 2025

Blogging the Silmarillion--of faith and resisting despair

I finished re-reading The Silmarillion last night and so will update the remainder of my prior posts on the book.

I don’t have a whole lot else to add, other than if you haven’t yet read The Silmarillion, you ought to make the attempt. In fact, I’ll say you must give it a valiant effort, if you’ve read and enjoyed The Lord of the Rings. It adds a tremendous resonance and depth to the events of that book, and to a lesser degree The Hobbit.

Upon re-reading my old posts I do have one thing to add.

In Blogging the Silmarillion I talked a lot about the problems Tolkien explores within his broader legendarium: Death, and the pursuit of deathlessness. Power, and possessiveness. Loving the works of one’s hands too much. But I wrote comparatively little on the answers offered in The Silmarillion. These include courage and companionship, but above all, faith. That there is, as Sam sees in the star of Eärendil far above the Ephel Dúath, light and high beauty for ever beyond reach of the Shadow.

Even if you’re not of religious faith it’s important to have it in a general sense. Faith in our basic goodness. Faith that life is worth living. And that something greater may always be waiting, even at the brink of disaster, as long as we do not give in to despair.

Eärendil’s perilous voyage to Valinor succeeds because he refuses to succumb to despair. Húrin and Túrin give in to it, and commit the ultimate capitulation of suicide. Despair is a tool of the enemy (think of the Ringwraiths, for whom its their primary weapon) and a deadly foe. But even a bitter defeat can be a step towards ultimate victory. It’s perhaps the greatest lesson The Lord of the Rings and The Silmarillion have to teach us.

Aragorn is a descendant of the faithful, a group led by Elendil who obeyed the law of the Valar and kept the friendship of Elves. The faithful preserved the seed of Nimloth the Fair, survived the drowning of Numenor and carried the seedling of the white tree to Middle-earth. And ultimately prevailed against the overwhelming might of Sauron.

Today our own fourth age brings with it new burdens and challenges. The struggle continues, possibly toward a long defeat. But as always, new hope arises.

Blogging the Silmarillion part 5: The Breaking of the Siege of Angband and (other) Myth-Busting

Blogging the Silmarillion part 6: Of Túrin Turambar and the sightless dark of Tolkien’s vision

Friday, January 3, 2025

Evil never dies: Parts 3 and 4 of Blogging the Silmarillion updated

Sunday, December 29, 2024

The Silver Key: 2024 in review

Sunday, December 22, 2024

Contribute a page

I’m just a guy (a classic JAG) who loves art, and is reflective by nature. So, I contribute reflections on art, and its relationship to life.

I can’t not do this.

Life and art are intertwined. We need myths, and stories. They entertain, but also offer a model for how to live good lives (because goodness is real, not an abstract concept). Art is a mirror on reality, sometimes clear and sometimes carnival fantastic, that gives life shape and meaning.

So that’s what I’m doing here, and in my writings elsewhere.

Anyone who brings art into being or contributes reflections on art and life has done something of value. Whether or not you find commercial success, I salute you.

Keep creating. Contribute a page.

Apropos of this PSA here is part 2 of Blogging the Silmarillion.

Thursday, December 19, 2024

Silmarillion re-read, link to part 1 and letter to Milton Waldman

|

| White ships from Valinor, Ted Nasmith. |

A few additional thoughts and comments on this most recent go-round.

I don’t know why I previously failed to mention Tolkien’s 1951 letter to Milton Waldman that leads off the volume. It’s like reading the cheat code for Tolkien’s greater legendarium. Interestingly this letter does not appear in the 1977 Houghton Mifflin first edition hardcover, but does appear in the gorgeous, Ted Nasmith illustrated 2004 second edition that I also own. Get this latter edition if you don’t already have it, there are nearly 50 illustrations and many appear in this volume for the first time.

Waldman was Tolkien’s friend and an editor at the publishing house of Collins, and the letter is more or less a lengthy summation of Tolkien’s argument that The Silmarillion and The Lord of the Rings should have been published together, or at least in conjunction, “as one long Saga of the jewels and the rings.” Of course that did not occur as The Silmarillion was published posthumously in 1977.

The letter contains a wonderful summation of what lies at the heart of the legendarium, “Fall, Mortality, and the Machine.” I am perhaps slightly more forgiving than others of Tolkien adaptations, even though I’d be content if we got no more, but I do believe that any faithful Tolkien adaptation must contain these elements. A Fall from God, the creator, Iluvatar; the problem of Mortality (and the problem of the pursuit of deathlessness); and the Machine, or the desire to dominate or coerce other wills and raze and bulldoze the natural world. Either implicit or explicit.

Monday, December 16, 2024

Re-reading The Silmarillion, and reviving my old Cimmerian posts

I'm enjoying it as much as I did upon my last re-read, which prompted me to revisit my old "Blogging the Silmarillion" series for the Cimmerian website.

Back when I was writing for The Cimmerian I used to run part of the post here and link to the rest. Unfortunately that has resulted in incomplete posts after that site was radically overhauled. Time to correct that by posting the full text here, which I fortunately retained.

Here's the series introduction, Cimmerian sighting: Blogging The Silmarillion.

I'll post the others as I work my way through the text, and possibly add a little additional commentary.

Sunday, December 15, 2024

Some interpretations of the ambiguous ending of The Green Knight (2021)

If you haven’t seen The Green Knight, and don’t wish to be spoiled, stop here before you enter the Green Chapel and its perils. Thou hast been warned.

The 2021 David Lowery written and directed film The Green Knight is an interesting, inventive take on the old poem “Sir Gawain and the Green Knight.”

It’s beautifully rendered. You can’t take your eyes off it. It also sticks with you, in part due to its ambiguous ending, which is very much open to interpretation.

Here’s a few thoughts I had from a recent re-watch. And yes, I seem gripped again by my annually recurring year-end fascination with King Arthur.

Needless to say spoilers coming.

***

Brief recap: The plot of The Green Knight (book and film) centers around the arrival of a massive, green-skinned and armored knight in King Arthur’s court on Christmas. He offers up a challenge: Any knight can strike him a blow with sword or axe from which he will not flinch, save that he will return the blow one year hence.

Arthur’s nephew Gawain, the youngest knight in the court, takes up the challenge and strikes a savage cut that sends his head tumbling to the floor. Then, to the horror of all in the hall, the mysterious figure picks up his severed head and turns to leave the stunned court, but not before reminding Gawain he must ride out to his chapel in a year to complete the challenge.

Gawain commits, and embarks on a series of adventures en route. In one of these he is given a green belt/sash that renders him invulnerable to any blow. An obvious, unforeseen advantage in a contest of his sort. But also, unfair and dishonorable.

In the poem, Gawain leaves on the sash, and receives a nick on the neck as a rebuke.

In the film, Gawain removes his sash after an agonized internal struggle, then turns to await the blow. One we’re not sure lands, because the film ends before we see it.

So, does Gawain get his head cut off?

I don’t believe that’s what actually matters. What does is his decision moments prior.

Earlier in the scene Gawain asks an existential question as he stares death in the face: “Is this really all there is?”

This is not (merely) a question concerning the end of his own life, but the possibility of a life without meaning, one ruled by the material laws of nature in which purpose and beauty and meaning are empty and meaningless, and death and decay our only masters. The type of world described by the dragon in John Gardner’s Grendel: “It’s all the same in the end, matter and motion, simple or complex. No difference, finally. Death, transfiguration. Ashes to ashes and slime to slime, amen.”

If he leaves on the sash, he will be invulnerable, but also will have fatally compromised the only virtue that matters in such a world: His integrity.

Gawain has a flash of what would happen should he leave on the sash: he becomes a king of a fallen kingdom, a dishonorable ruler, haunted by his choice over the long years until the kingdom falls, corrupted.

Ultimately he chooses honor. Does that cost him his life?

The film offers some clues. “Well done my brave knight,” the green knight says, after Gawain removes the sash. And then, the final cryptic line of the film: “Now, Off With Your Head,” which obviously implies he’s a goner.

After all, a blow is due in return per the sacred rules of the game. Honor demands it.

However, the Green Knight delivers the final line with a good natured, light-hearted spirit, indicating that any blow will be only lightly given, which would make it true to the poem.

As important as this (obviously) is for Gawain and his future, I’m not sure it matters either way.

Even if Gawain loses his head, the message of the film can be interpreted as profoundly hopeful.

Let’s start with the idea that the Green Knight represents nature. If so, his acknowledgement of Gawain’s selfless act implies there is honor embedded in nature. It is not an abstract, empty term rendered meaningless by postmodernism, it is as real as the grass under our feet, the rotation of the earth and its seasons. We just have to make the choice.

Though there is a far bleaker interpretation. There may be honor but it ultimately doesn’t matter, nature is going to kill you in the end anyway. It’s all a cosmic joke.

But maybe we should still act honorably anyway, because doing so is its own reward.

Regardless, I believe Gawain's transformation from shiftless coward to noble knight suggests that facing death with dignity is essential to living a meaningful life.

What do you think?

I welcome any thoughts on this.

Friday, December 13, 2024

Where Eagles Dare, Iron Maiden (for Nicko)

|

| Job well done. |

When Nicko joined Iron Maiden in 1982 there were skeptics. He was replacing Clive Burr, a terrific player who had been there since Maiden’s debut album, and joining a well-established band that had just put out the wildly popular Number of the Beast.

Nicko had to make an impression. And he did, on the very first song of his first studio album with the band, “Where Eagles Dare.” An awesome, driving tune kicking off side A of Piece of Mind (1983).

It’s telling that the first sounds you hear on this classic album are Nicko’s thunderous drums. He brought a new level of heaviness and intensity to the band, and remained Maiden’s drummer for 42 years, until age and the residual effects of a 2023 stroke forced him to hang up the drumsticks.

At 72 Nicko has more than earned his retirement.

I’m glad I got to see Maiden and Nicko one last time earlier this year. Our metal heroes are aging, no guarantees of tomorrow.

Saturday, December 7, 2024

Of the year in writing, and reading--memoir update and more

Friday, December 6, 2024

Season of the Witch, Grave Digger

Tuesday, December 3, 2024

Sons of Albion awake: Of J.R.R. Tolkien’s The Fall of Arthur and Iron Maiden

|

| You'll probably want to read this. |

We feel their powerful call, and many have sought to capture their magic in diverse adaptations. These include authors separated by long gulfs of time—Malory and T.H. White, for example—and artists working in very different mediums.

J.R.R. Tolkien and Iron Maiden.

I just got finished reading Tolkien’s The Fall of Arthur. It’s a curious little volume, 233 pages, of which the actual centerpiece poem is incomplete and only comprises 40 pages. The rest is critical apparatus by Tolkien’s son Christopher.

But what a poem it is.

40 pages of 14th century alliterative verse rendered into modern English metre, telling the story of Arthur’s journey into far heathen lands before he is summoned back to Britain to quell an uprising by the traitor Mordred. Of Guinevere’s flight from Camelot and a great sea battle.

This is no tale of formal courtly love or restrained codes of chivalry, but resembles something out the pages of The Iliad, the Goddess singing of the rage of Achilles:

Thus the tides of time to turn backward

and the heathen to humble, his hope urged him,

that with harrying ships they should hunt no more

on the shining shores and shallow waters

of South Britain, booty seeking.

As when the earth dwindles in autumn days

and soon to its setting the sun is waning

under mournful mist, then a man will lust

for work and wandering, while yet warm floweth

blood sun-kindled, so burned his soul

after long glory for a last assay

of pride and prowess, to the proof setting

will unyielding in war with fate.

There is no magic, no romance, just vengeance, hard combat, lust, and doom.

… then a man will lust for work and wandering… so burned his soul after long glory. Not exactly Bilbo comfortably enjoying cakes and tobacco at Bag End. Yet Tolkien wrote The Fall of Arthur contemporaneous with his much more famous work.

Tolkien began the poem in the early 1930s and there is evidence to suggest he may have continued working on it as late as 1937, when The Hobbit was published. He spent a lot of time getting the words right, and his effort was not wasted—its words ring with power. Christopher says his father drafted some 120 pages before settling on the final text presented in the book. “The amount of time and thought that my father expended on this work is astounding,” he says.

Given the effort expended it remains a mystery why Tolkien abandoned the poem, though Christopher offers up a possible explanation: He was turning his whole thought to Middle-Earth.

After the publication of The Lord of the Rings Tolkien expressed a desire to return to the poem, but the effort failed. It’s a shame the poem remained unfinished but Tolkien’s unbounded genius outstripped his available hours.

But the extant work is remarkable, and as Christopher demonstrates in the additional material served as likely inspiration for the great Middle-Earth legendarium, including the voyage of Earendil and the fall of Numenor.

|

| Arthurian Eddie. |

Arthur was taken to Avalon to be healed after his great wound suffered at the hands of Mordred at Camlann. The story from there varies; in some versions he does not make the voyage but dies and is interred in an abbey graveyard at Glastonbury. But in others he seems to reach the fabled isle, where one day he will return, healed, to unite a divided land.

Maiden refers to the legendary properties of the isle in “Isle of Avalon” off of 2010’s The Final Frontier.

The gateway to Avalon

The island where the souls

Of dead are reborn

Brought here to die and be

Transferred into the earth

And then for rebirth

This same Isle of Avalon prefigures Tolkien’s Tol Eressea, the Lonely Isle, accessible only by a Straight Path out of the Round World denied to mortals, that led on to Valinor.

Arthur, gravely wounded, bides in Avalon/Tol Eressea. His return is promised in the old rituals and the enigmatic enduring standing stones of Britain, as depicted in “Return of the King,” a track appearing on the expanded edition of Bruce Dickinson’s 1998 solo album The Chemical Wedding.

What is the meaning of these stones?

why do they stand alone?

I know the king will come again

From the shadow to the sun

Burning hillsides with the beltane fires

I know the king will come again

When all that glitters turn to rust

The song is a powerful cry for Arthur’s return, one that I feel.

We’re all engaged in the eternal struggle. As human beings we're possessed of individual desires and wants and enjoy our freedoms, but must balance that as members of a civilization that provides purpose and joint safety--and in exchange saddles us with restrictions and obligations. The Arthurian myths speak directly to this great tension.

Arthur is a man with earthly desires, including his great love for Guinevere, but must subsume them to greater obligations owed to his kingdom. Launcelot is a heroic figure whose martial prowess and love for Guinevere can be viewed as the Chivalric ideal, but his base desires and human weaknesses undo a kingdom.

All the same struggles play out today. There is no clean resolution, just a balance that must be struck with compromise.

I think we’ve have tipped too much into individualism. We create and curate our own virtual realities in our smartphones. We distrust institutions. Civic engagement has sharply declined. Some of this institutional skepticism is warranted. But if everyone reverts to selfish individual interests the center cannot hold, and civilization falls apart.

We need the return of a king to unite this fragmented land.

In “The Darkest Hour” Bruce/Winston Churchill exhorts the besieged people of England to turn their ploughshares into swords and take up arms against tyranny (“You Sons of Albion awake, defend this sacred land”). Perhaps we one day we may unite under a common cause, the idea of Arthur, and create a new shining kingdom from the wasteland, a “Jerusalem” on earth:

I will not cease from mental fight,

nor shall my sword sleep in my hand,

till we have built Jerusalem

In England's green and pleasant Land.

Thursday, November 21, 2024

Immaculate Scoundrels by John Fultz, a review

|

| An immaculate cover. |