"Wonder had gone away, and he had forgotten that all life is only a set of pictures in the brain, among which there is no difference betwixt those born of real things and those born of inward dreamings, and no cause to value the one above the other." --H.P. Lovecraft, The Silver Key

Tuesday, May 13, 2025

Here's something cool: Tom Barber painting donated to Andover (NH) public library

Sunday, May 11, 2025

Rock and metal shows starting to accumulate

When the year began I had just one show on schedule, Ace Frehley on Jan. 30 at the Tupelo Theater in Derry, NH. Possibly a second in Lotus Land, a Rush tribute, though that might have been an early year purchase.

After committing to Blind Guardian on Wednesday, Nov. 26 at the Worcester Palladium a couple days ago, I’m up to eight. In this age of artificiality I crave live performances. I need a regular metal and hard rock fix, and Spotify alone doesn't cut it.

I’ve never seen Bruce Dickinson solo so that one intrigues me the most. Hairball (a band that covers various 70s-80s metal acts, including costumes etc.) should be a blast in a wild venue. Foreigner’s Journey is another tribute act of, as you might guess, both Foreigner and Journey. I’ve seen them once before and the lead singer sounds uncannily like Steve Perry, less like Lou Gramm.

And yes, I did see Ace Frehley 2x this year. I might yet add 1-2 more (shows, not Ace Frehley).

Thursday, Jan. 30

Ace Frehley

Tupelo Theater, NH

Friday Feb. 14

Lotus Land

Cabot Theater, Beverly

Saturday March 15

Ace Frehley

Blue Ocean, Salisbury

Friday June 13

Foreigner’s Journey

Blue Ocean, Salisbury

Thursday Sept. 11

Bruce Dickinson

Citizens House of Blues, Boston

Friday Sept. 26

Judas Priest and Alice Cooper

Holmdel, NJ

Saturday Oct. 11

Hairball

Hampton Beach Ballroom Casino

Wednesday Nov. 26

Blind Guardian

Worcester Palladium

Wednesday, May 7, 2025

Robert E. Howard, The Life and Times of a Texas Author: A review

- Oliver does a fine job setting up Howard’s time and place—the actual town of Cross Plains. It offers rich detail of his family history/parents and settlings in the United States.

- There is some great material here on Howard the poet—his love of verse, his early sales, and being one of the most prolific poets in WT history. Howard’s poetry even received rare praise from mercurial Weird Tales editor Farnsworth Wright. Fans often forget this or overlook his wonderful poems.

- New to me; Howard’s deliberate construction and cultivation of an Irish identify (pp. 197-198); I knew about his strong Gaelic interests but not how far he adopted them into his own life—singing old Irish songs, Gaelicizing his middle name, etc.

- His youthful, beer-swilling trips with Smith and Vinson as detailed in the Junto (p. 215), told here evocatively and dude-bro awesome by Oliver.

- Oliver does a nice job introducing “The Shadow Kingdom” and its important place as the origin of sword-and-sorcery but also one of Howard’s most poetic and vivid stories, as well as how popular it was with WT readers and editors (my ego is pleased to find myself cited here, and elsewhere, in the work—pp. 245-246).

- Howard’s fatiguing medical condition is covered here with more research, care and nuance than DVD.

- There are several new pics of REH I had not seen before. This was a very pleasant surprise.

- We get some well-placed details on the Great Depression, focused on Cross Plains and the closure of its two banks in 1931 (p. 308).

- Howard’s love of westerns and the role of the frontier in his books. Although he wrote straight two-fisted westerns he also wrote some weird westerns, a genre for which he is considered the founder (p. 315)

- I enjoyed the detail on Margaret Brundage’s artistic process. A prolific cover artist for Weird Tales, she would actually read the stories, pick the scenes that seemed most salacious/sexy, draw them using pastel chalk on canvas, and tack the image to a wooden frame before dropping them off at the WT office (p. 338).

- Black Mask, Dashiell Hammett and the birth of hard-boiled detective, meting out tough personal justice outside the law. Howard wrote his own hard-boiled detective stories but never loved the form and it was his least successful literary foray (p. 350).

- Howard getting half-checks from a struggling Weird Tales before these too ceased due to the magazine’s financial woes (p. 412). If I had read before that WT was cutting Howard half-checks with the promise to pay the rest later if so I had forgotten this detail.

- Howard’s love for the Texas landscape and its barbarian ethos, which likely would have been his next literary venture (p. 436).

- Oliver’s speculation that Hester’s death provided the occasion for Howard’s suicide and was not necessarily the inciting incident; I agree, though would add it was the result of an irreconcilable clash of values (p. 455).

- Details about a will Howard wrote near the end of his life which reportedly bequeathed all his worldly possessions to friend Lindsey Tyson. And destruction of said will. Oliver says this may have been gossip, not fact.

- A nice summation of Howard’s character by Price and his circle of friends and WT collaborators, post-suicide. This was sad, especially the letters of remembrances and posthumous praise to the Eyrie from heartbroken WT readers (p. 466).

Saturday, April 26, 2025

The day Hannah met Sam Gamgee (and called to tell me)

|

| My Sam Gamgee is indeed a reflexion of the English soldier, of the privates and batmen I knew in the 1914 war, and recognized as so far superior to myself. --JRRT |

But that’s not the coolest part.

The coolest part was, she called to tell me. Breathlessly and right away. Because she knew I’d appreciate it more than anyone.

Walking through the campus of Endicott College this week Hannah saw that Sean Astin was due to speak to the students, that very night. A fortuitous find, if you happen to revere The Lord of the Rings and The Goonies as I do, and she does.

I showed her and her sister the films back in the day and we’ve watched them together a few times since. Hannah has gone on to introduce her friends to them.

It’s nice to know there is something of a mini-me out in the world.

It’s unnerving when your kids go out on their own, and take one step further from home than they’ve ever been (points for guessing the reference). When my phone rang at 4 p.m. and I saw it was Hannah, my heart raced a bit… it was an odd hour to call and I immediately thought something was wrong.

But it was very right.

“You’re never going to get what just happened!” she said. I was thrilled that she’d be seeing a star who brought us so much joy on screen… but even more happy that she thought to call me.

Hannah is like this. She’s naturally social, communicative, with a much better sense of this than I possess. Last year she started working as a teacher at Landmark, a school that specializes in children with high-functioning disabilities. A great fit, given her skillset.

She’s still close enough to come home and do her laundry and have dinner with her parents from time-to-time. But when she’s away she picks up the phone … and sometimes we talk about One Eyed Willy, Chunk, and “Baby Ruth.”

I’m thrilled she got to see the actor who played so many great characters we love, in person. But more than that, I’m happy she remembers her old man.

It’s a good reminder that I need to pick up the phone more often. I taught her some things … and she teaches me as well.

***

In other news of a biographical nature, I'm working my way through the new Robert E. Howard biography Robert E. Howard: The Life and Times of a Texas Author, by Will Oliver, and greatly enjoying that. My early impressions after about 200 pages: It is thorough, deeply researched, and walks a middle path between the likes of L. Sprague de Camp's Dark Valley Destiny and Mark Finn's Blood and Thunder.

I am also getting close to the end of my heavy metal memoir.

Friday, April 18, 2025

Cauldron Born: Born of the Cauldron

Thursday, April 17, 2025

Death gives meaning to life

Roy Batty is pissed. He is the peak of what a replicant can be. Brilliant and reflective. Handsome and powerful, a physical specimen.

But despite his near perfection—his is a light that burns twice as bright—he is, like the flesh and blood humans he is designed to replicate, mortal.

His maker, Dr. Eldon Tyrell of Tyrell Corporation, has programmed the replicants with a short lifespan. Roy wants more, telling his maker, “I want more life, fucker” (one cut of the film substitutes, “father,” which makes the point of who he is addressing even more blatant).

But more life is beyond Tyrell’s power. So Roy crushes his head like an egg.

His rage is understandable. We’ve all raged at the finitude of life. If you live long enough you see grandparents, aunts, parents, friends--hopefully not children—perish, and deal with grief of separation that may be eternal.

Roy’s life burns twice as bright, as does his incandescent rage at his maker. But is it possible he is mistaken, his anger misplaced? And that he should be, perhaps, grateful?

Roy’s death is beautiful. The speech he gives, reportedly ad-libbed, is perhaps the most powerful and poignant scene in the film. Ridley Scott made some interesting, purposeful choices with how he filmed it.

Death is necessary. Without it, life lacks meaning.

Ernest Becker in The Denial of Death explains that we are limited beings with unlimited horizons, and so live in a constant state of terror (often subliminal) about our own impermanence and insignificance. That all we do—witnessing attack ships off the shoulder of Orion, for example—will all be lost when we pass. And nothing will have come of it.

Yet a life without death represents a different kind of terror. In The Denial of Death Becker describes the concept of a transference object, which is a person, institution, or idea onto which an individual projects their need for meaning, security, and immortality.

My personal transference object is J.R.R. Tolkien. I happen to like very much what JRRT has to say about death. Tolkien writes that Iluvatar, the creator, gave Men the gift of mortality, setting them apart from the Elves, who are bound to the world until its end. Elves may be immortal, but they are also weary and burdened by time; their spirits are tied to the fate of Arda (the world), and they experience sorrow and loss without the release of death. Men, on the other hand, are granted the ability to leave the world—and their destiny beyond it remains a mystery, even to the wise.

This idea is most clearly articulated in The Silmarillion, where death is described not as a curse but as a “gift” that allows Men to transcend the world and return to Iluvatar in a way the Elves cannot. But as Morgoth corrupts the world, Men come to fear death, forgetting its intended grace. Instead the Numenoreans strive in vain for immortality.

Tolkien calls death a great gift, the greatest given to men. It breaks the cycle of worldly attachment and offers the hope of something greater. In Tolkien’s Catholic worldview, this aligns with the idea that death is a passage, not an end. It is the one thing that prevents stagnation, that pushes us toward humility, courage, and faith.

Death, for Tolkien, is the door through which true transcendence is possible. Interestingly, both Becker and Tolkien believed that human culture, politics, the stuff around us, was not the way to ultimate meaning. We must shift our perspective towards the cosmic. This mirrors my pursuit of identifying my values and searching for meaning in the symbolic world of ideas rather than the physical. We'll never find meaning here, not even in rings and Silmarils.

Death makes life meaningful, because without it spending time with people does not come with a cost. Without death, any achievement could be unlocked in time. Everyone would eventually share the same experiences, and memories, as they’d explore every crevice of the planet. Because you could in theory do everything, nothing would be unique, or special. Including any given human life.

You would never have to think about whether you want to spend your time reading a book, or watching a movie, because you could consume all of them. You could choose not to spend time with a loved one and instead watch 200 straight hours of Netflix, because you could spend as much time as you wanted, later. I am not sure love as we know it would even exist; we’d get bored with our life-mate and take up the next.

So death is a gift. It’s a mighty paradox, and I almost feel ashamed, flippant, at writing that. I am quite certain that when I lose someone dear, I will be devastated. I can’t even contemplate my own death, and potential eternal separation from everyone I love.

Yet on a relatively rational day like today I believe it to be true. The abstract knowledge of my own death motivates me to appreciate the warm spring sun coming through the window on my face. It motivates me to write this essay. “Blessed” with immortality and lacking any urgency, why not write it tomorrow, or tomorrow, or … never?

Part of me wonders if I’m not just rationalizing my own terror, the knowledge that I one day too will depart down The River of No Return.

Would I accept immortality were it offered to me, if some AGI were able to stop aging and keep us forever young? I don’t know.

But today, at least? I believe death is a gift.

Roy’s memories are not lost like tears in rain because his story remains. Deckard is the witness, and we are the witness of the film. His death and all deaths are tragic of course, but it’s also the ultimate gift for humanity, which makes more Roy never more human than at that very moment.

And perhaps his soul, symbolized by the flight of the dove, is saved.

***

Holy crap I’m writing about some heavy topics these days. I seem to have no choice, just following the muse. I suppose this is what happens when you’re north of 50 and an empty nester, dealing with a death in the family and others suffering with old age. But the spring is here and I’ve got a lot to be grateful for.

Friday, April 11, 2025

The Knight stands against nihilism

|

| Excellent book... unfortunate cover blurb. |

“It is honor, Able. A knight is a man who lives honorably and dies honorably, because he cares more for his honor than for his life. If his honor requires him to fight, he fights. He doesn’t count his foes or measure their strength, because those things don’t matter. They don’t affect his decision.”

The trees and the wind were so still then that I felt like the whole world was listening to him.

“In the same way, he acts honorably toward others, even when they do not act honorably toward him. His word is good, no matter to whom he gives it.”

--Gene Wolfe, The Knight

Character matters. There is truth in the world of ideas.

I was listening to a podcast the other day. One of the guests--an author, self-described philosopher, and entrepreneur—concluded a view of the world I find abhorrent: Objective truth does not exist, values are manufactured and none better than others, and the purpose of life is maximizing personal happiness.

I’m leaving this dude’s name out because I don’t know him, and I’m attacking the idea, not the individual. But I do wonder: How do you end up in your mid-50s endorsing nihilism? Cheerily admitting there are no such things as absolute moral values … which means that everything is in theory permitted? It’s a train of thought that leaves dragons hoarding wealth they’ve ruthlessly abstracted from others, swelled with hubris, unable to see that their gold is derived from the thankless labor of uncountable generations who built civilization, created the human project from squalor, and allow for the existence of privileged coastal millionaire elites.

Few openly admit to nihilism, but many act that way. “I’ll extract wealth from the less fortunate, because no one is watching. And after all, it’s technically legal and I can get away with it.”

We each have the freedom to construct our own meaning and live our own lives as we see fit … except when that freedom infringes on or destroys other’s lives. The strong are obligated to lift up the sick, weak, and needy. Because it’s honorable to do so. And I would argue, an obligation that is an objective truth of the human condition. How long does this last if everyone behaves like a selfish douche canoe?

Imagine if Able of the High Heart was a nihilist? It would make a much different book than Gene Wolfe’s The Knight.

The story centers around a small boy who enters through a portal from our world to Mythgarthr, a world of high fantasy, gods, magic, monsters… and stouthearted knights. After an encounter with an elflike being, Disiri the Mossmaiden, Able rapidly grows into a powerful man and embarks on a journey into knighthood.

This sudden transformation means we get a uniquely compressed character arc. Able goes from an adolescent experiencing the vicissitudes of life, to young man called to perform duties to others, to grown man called to service to his own heart and conscience. From learning from others to teaching others the way. As we all should, objectively. Because if we don’t do this, we’ll leave the next generation in shambles. Which should concern you unless you’re a nihilist and think that death and life are one and the same.

Of course, we’re never going to be perfect. We throw away much for pleasure. Reject responsibility to others because it doesn’t maximize our momentary well-being. As Able does with the vixen of the woods. This is part of growing up. I think we all have to indulge in pleasures of the flesh.

But at some point adults realize it’s time to fight the dragon.

As noted recently I struggle with Wolfe. I find him needlessly opaque and allusive, at times impenetrable. Not so much with The Knight, which I enjoyed, if not unreservedly. Even here Wolfe does not make the journey easy for the reader. The story is told in an epistolary/letters from Mythgarthr to modern earth style which I don’t love, which leaves important sequences glossed over or relegated to the background. Able often for example will completely gloss over a battle, and only later do we realize the extent of his heroism through offhand remarks from observers after the fact.

… but that’s sort of the point, isn’t it? Knights with a code of honor don’t crow about their accomplishments. They don’t virtue signal on Instagram and sell self-help books as they lead deeply insulated, selfish lives. That would be … dishonorable.

There’s much other great stuff in here that make the The Knight a memorable journey. Wolfe-ian symbols I’m quite certain I failed to grasp. When Able plunges three times into a deep pool, beyond air and endurance, to retrieve his armor and sword, and hears the horns of Aelfrice/elfland, we feel a mythic power we cannot articulate, literally and metaphorically deep. But one lesson we can be sure of: Unless you confront the metaphorical dragon it becomes terribly real.

I’m sure I will tackle The Wizard after a palate cleanser. For now something a bit lighter is in order.

Sunday, April 6, 2025

My daughter has a Substack. Which is very cool.

Saturday, March 29, 2025

Gene Wolfe is intimidating. The Knight is not. I also recommend smoked brisket.

I’ve got a Gene Wolfe sized hole in my reading.

Wolfe is generally accorded of the most respected and literary fantasy authors--ever. Readers are enthralled by his fierce intelligence, incredible imagination, vivid world building and 3D characters. But even his most ardent fans acknowledge he can be tough, reading his stories not unlike grappling with water or a Brazilian Jiu Jitsu master. Half of the reviews of The Book of the New Sun are people who don’t seem to understand what’s going on yet declare that “you have to read this.”

Weird.

As for me, I read the first Book of the New Sun, The Shadow of the Torturer, some 10-12 years ago. Read is perhaps generous; I muddled through, and after closing the cover was left puzzled—not defeated, but feeling like I didn’t grasp it all and probably needed a second attempt. I’ve enjoyed a few of Wolfe’s short stories and deflected off few others; “The Sailor Who Sailed After the Sun” in Grails: Quests of the Dawn left me scratching my head and disappointed, but “A Cabin on the Coast” from the Year’s Best Fantasy 11 was terrific. I also liked “Bloodsport (not the one with Jan Claude van Damme) in Swords and Dark Magic well enough.

The best thing I’ve read by Wolfe is his essay “The Best Introduction to the Mountains,” a moving and poetic elegy to JRR Tolkien that you can read online in its entirety. Wolfe blends a poem by Robert E. Howard into the piece, S&S fans. Writes Wolfe of Tolkien’s greatest literary legacy, “Freedom, love of neighbour, and personal responsibility are steep slopes; he could not climb them for us—we must do that ourselves. But he has shown us the road and the reward.”

Check it out.

But as for his fiction… I’m decidedly mixed. Wolfe loves unreliable narrators and I’m generally not a fan of this device which perhaps explains my ambivalence. But I haven’t given up on Gene, and so decided to have another go with what others have described as his most accessible work—his The Knight and The Wizard, two novels often published together.

I’ve begun reading The Knight. And am happy to report, it’s fantastic. Teenage boy is transported into a magical realm and an encounter with a lusty sprite transforms him into powerful man, and a knight, Sir Able of the High Heart. It’s a straightforward narrative… yet there are clear Wolfe-ian undertones of, a lot more going on under the surface than our narrator understands.

I’m not quite halfway through and will have a review up here on the blog later.

***

In other happy news Spring has finally arrived in New England. I broke out the smoker yesterday and made a brisket that was decidedly on-point. And enjoyed it with my father. No sides necessary, other than beer. I'm getting better with the smoker, which really comes down to low and slow. All good things take time to make.

Tuesday, March 25, 2025

Facebook ripped me off

I punched my name into this handy plagiarism detection tool published by The Atlantic, and like millions of other authors discovered Mark Zuckerberg ripped me off. The nerve of this douche!

|

| There I am! Above the whiskey. Of which I now need a few shots. |

In case you missed the recent news, “Meta and its founder and CEO Mark Zuckerberg deliberately and explicitly authorized a raid on LibGen—and Anna's Archive, another massive digital pirate haven—to train its latest AI model.” Millions of books have been ingested into Llama 3 without author compensation, or even notification.

What makes it even worse is that the fine folks at Facebook (I almost wrote that without a sneer) could have put some thought into the decision. Taken a few extra weeks to do the right thing. But instead chose to behave like Somali pirates operating on the open ocean.

What the fuck, Zuck.

There is of course complexity to this. How does fair use apply to the output of generative AI? Is feeding a machine training data the equivalent of a person reading? Will slowing AI development with more rigorous author protections and safety guardrails put us behind foreign competitors like China?

But that’s a battle for someone else to fight. Me? I’m tired of the techo-obfuscation and the excuse-making. This is pretty close to outright theft. Facebook could have done this the legal and proper way but its leadership team chose to operate like immoral assholes. Which should surprise no one.

I've written before that I'm not a fan of generative AI, even though I believe it has incredible potential and is here to stay. It’s just beyond galling that big companies like Meta and OpenAI scrape data from wherever and whomever they want and then sell it back to you in the form of subscription products. And then rigorously defend their own gated fiefdoms with impenetrable legalese and teams of lawyers.

The moral of the story: Laws don’t apply to big companies like they do individuals.

Honestly I am not THAT pissed. Just looking on, feeling bemused, disappointed and disempowered, sort of like the victim of a drive-by egging. Perhaps Llama 3 will now create some kick ass S&S haikus using the genre elements I outline in Flame and Crimson. Maybe there will be a class action suit and I will be entitled to a $3.87 payout after the lawyers take their share. We’ll see.

Friday, March 21, 2025

The Rage, Judas Priest

It's a testament to the greatness of British Steel that a song as good as "The Rage" is buried deep on side 2. Wait, do people still refer to albums, and sides? I do.

There is a reason this album is a stone-cold classic. To use a sports analogy its bench is deep ... I don't think it has one weak track and it all sounds awesome, songs stripped down to bare steel. You will find an album "none more metal," to paraphrase one Nigel Tufnel.

The start of "The Rage" is quite unexpected, a funky solo bass intro followed by a jazzy, swinging drum beat that lulls you in to a false sense of security. Where's the rage?

But wait, it's coming. An angry, fist-thrusting metal assault, pounding beat and heavy guitar backed by Rob Halford's soaring vocals.

The breakdown at the end with the rapid fire (snare? I'm not a musician) is divine. It sounds like a machine gun. See 4:06 of the below video.

Maybe it is. Happy Metal Friday.

When we talk with other men

We see red and then

Deep inside our blood begins to boil

Like a tiger

In the cage

We begin to shake with rage

Thursday, March 20, 2025

The Ring of the Nibelung/Roy Thomas and Gil Kane

|

| The Ring is mine! |

But I haven’t ever seen the opera nor read a full literary treatment of the work. And was overdue to scratch this niggling itch … but wanted to have some fun, with a low bar to entry. And so, I scooped up a treatment I did not know existed until quite recently: Richard Wagner’s The Ring of the Nibelung, the complete graphic novel as adapted by the great Roy Thomas and Gil Kane, with Jim Woodring.

This was enjoyable. I plowed through it in just a few hours over a few nights. It’s a product of DC Comics, released in 1991, and checks in at a relatively hefty 191 pages. It includes some welcome introductory material, including a foreword introducing the biography and talents of the authors, and an introduction to Wagner’s opera cycle by Brian Kellow of Opera News.

The Ring of the Nibelung is a somewhat complex story, with four acts/operas (Wagner prefers music dramas) spanning long periods of time, told through different sets of characters ranging from gods, giants, and dwarves to the heroic albeit mortal race of humans known as Nibelungs. It starts with the creation of the world, and ends with its downfall at Ragnarok. The centerpiece is the story of Siegfried, a mortal hero sent to slay a dragon, reclaim the gods' stolen gold and rescue the Valkyrie Brunnhilde. These stories are bound together by a golden ring that grants its wearer dominion over the world. Yes, there are some Tolkien parallels here, which JRRT denies and to be fair he likely drew on Wagner’s common influences, not the operas. But we’ve got a greedy dragon hoarding wealth, a precious ring fought over by two brothers (one of whom kills the other to take it for himself), a broken sword reforged, and many other familiar elements.

Overall it's a gorgeous, epic, deeply thematic story well told by Thomas—and as you’d expect from his pen, it moves. Kane’s artwork is marvelous, beautiful, comic booky and muscular but not garish. The men are jacked and the women beautiful. Rather than me attempt to word-paint here are some of the panels:

What does it all mean? There’s a lot to dig into, too much for me after one rapid reading of an adaptation in graphic novel form. But The Ring is undoubtedly a Great Story, and like all great stories contains truth. I’m quite fond of Sir Roger Scruton’s “Reflections on The Ring of the Nibelung,” which he describes as a story for “modern people, for whom the path to heroism is overgrown.”

From that essay:

Wagner’s story of gods and heroes, of giants and dwarfs, is not a fairy tale. It is addressed to modern people, who have lost the ways of enchantment, and for whom the path to heroism is overgrown. It is a story in which law and love, power and property are all caught up in a life and death struggle between the forces that govern the human soul.

Love without power will not endure, and power without law will always erode the claims of love. We live this paradox, and without the gods to maintain the moral order the burden of it falls entirely on our shoulders.

Gods come and go; but they last as long as we make room for them, and we make room for them through sacrifice. The gods come about because we idealize our passions, and it is by accepting the need for sacrifice on behalf of another that our lives acquire a meaning. Seeing things that way we recognize that we are not condemned to mortality but consecrated to it. Such, in the end, was Wagner’s message. Yes, the gods must die, and we ourselves must assume their burdens. But we inherit their aspirations too: freedom, personality, love, and law. There is no way in which we can achieve those great goods through politics, which, if we put too much faith in it, will inevitably degenerate into the kind of totalitarian power enjoyed by the dwarf Alberich. But we can create these things in ourselves, and we do this when we recognize the sacred character of our joys and sufferings, and resolve to be true to them.

For more reading and listening, check these out:

Reflections on “The Ring of the Nibelung”

Wagner Götterdämmerung - Siegfried's death and Funeral march Klaus Tennstedt London Philharmonic

Saturday, March 15, 2025

The Empress of Dreams—an (overdue) appreciation of Tanith Lee

“Is the cup ensorcelled?”“I cannot definitely tell you,” Jandur answered. It was a fact, he could not.“It is—what is it?”“Alas, I cannot say. Mystical and magical certainly.”“Does it affect all—who—touch it?”“In various ways, it does. Some weep. Some blush. Some begin to sing.”“And you,” said Razved, with another warning note suddenly entering his voice; that of jealousy, “what do you feel when you take hold of it?“Fear,” Jandur replied simply.“Ah,” said Razved. “It is not meant for you, then.”

Razibond’s face was now a marvellous study for any student of the human mood. It has passed through the blank pink of shock to the crimson of wrath, sunk a second in superstitious, uneasy yellow, before escalating into an extraordinary puce—a hue that would have assured any dye-maker a fortune, had he been able to reproduce it. More than this, Rozibund had swollen up like a toad. He cast his wine cup to the ground, where it shattered, being unwisely made of clay, and, disdaining his knife, heaved out a cleaverish blade some four feet long.

Sunday, March 9, 2025

We're living in an outrage machine

|

| Tanith Lee = anti-outrage. |

Friday, March 7, 2025

Monday, March 3, 2025

Martin Eden (1909), Jack London

|

| A great voyage of the soul... |

1. JRR Tolkien

2. Robert E. Howard

3. Jack London

4. TH White

5. Stephen King

6. Ray Bradbury

7. Bernard Cornwell

8. Poul Anderson

9. Karl Edward Wagner

10. HP Lovecraft

Reading London is akin to receiving an electric shock. The intensity with which he writes is almost unrivaled. In fact, there’s really only one author I’ve encountered who writes with the same poetic, romantic verve, great splashes of color and blood and rage and wild passion: Robert E. Howard.

I didn’t necessarily think Martin Eden would deliver the same visceral experiences as The Call of the Wild, The Sea Wolf, or The Star Rover, but as it turns out, it did. These are mostly contained in the heart and mind of the titular protagonist, though there are some all-time savage fistfights. But even with no swordplay or sorcery, I literally aloud mouthed, “god damn” after reading various lines and passages--probably at least a dozen times.

Why read Martin Eden if you a sword-and-sorcery fan, or a fan of REH?

Howard was directly influenced by London, in all ways.

If you want to know how Robert E. Howard felt, read Martin Eden.

If you want to know how Howard wrote, read Martin Eden.

How Howard struggled with life, with relationships, with his disappointment for the world--it’s all here, in this book. Martin Eden is almost as vital to understanding Howard as his personal correspondence, or One Who Walked Alone. IMO.

How can I make such a wild declaration? Martin Eden was the chief influence on Howard’s own autobiographical novel, Post Oaks and Sand Roughs. It likely influenced Howard’s life choices and how he viewed himself, too. REH scholar Will Oliver does a nice job tracing these influences in his essay “Robert E. Howard and Jack London’s Martin Eden: Analyzing the influence of Martin Eden on Howard and his Semi-Autobiography” (The Dark Man: Journal of Robert E. Howard and Pulp Studies, Vol. 11, Issue 1, June 2020). Which I sought out and read after finishing the book.

Martin Eden is a writer, a frustrated romantic, a boxer. He worked long hours in soulless jobs while wanting to do something else. The book is a story of romance colliding with commerce. Just as Howard was foiled by the whims of magazine publishers and the late payments of Weird Tales, so too is Martin Eden consumed with these struggles, living on the edge of poverty and needing to work back-breaking jobs that left him too tired to write. Yet he pressed on, because he refused to let passion and truth succumb to conformity and mindless work.

But it’s a brutal struggle, and a tragedy, just as Howard’s life was.

Martin Eden is many other things besides. A critique of early 20th capitalism, its long and inhumane working conditions. A critique of class, the cultural elites who look with scorn upon the working-class men and women who actually make the world go round. It’s a critique of the weakness of people, who are fickle and disloyal and petty.

Eden’s great love, Ruth, abandons him when he needs her most. When he finally meets with success the world comes crawling back but Martin sees through the grift and shallowness. He’s like Conan, a barbarian at odds with corrupt civilization. A rough and uncultured sailor, Eden desperately wants to be civilized, and spends the whole book in this pursuit. He makes, it, but at the expense of his soul. When he finally learns of its cultured ways, “the gilt, the craft, and the lie,” it breaks his heart.

“I’m no more than a barbarian getting my first impression of civilization,” he observes.

I won’t it spoil any further, just to add if not already apparent: Martin Eden=Recommended.

Wednesday, February 26, 2025

Rest in peace James Silke

James Silke, best known in S&S circles as the author of the Death Dealer series, recently passed away. He was 93 and lived a full and varied life as a photographer, writer, art director and more.

I'd been slowly working my way through the Death Dealer series and am posting here links to my prior reviews. These unfortunately are not great books, certainly not as good as their fantastic Frank Frazetta cover art ... but they do possess a ridiculous charm of their own, a bit of a "WTF did I just read?" unpredictability that makes them ... notable.

Sword-and-sorcery’s endgame: James Silke’s Prisoner of the Horned Helmet

“This goes to 11:” A Review of Death Dealer Book 2: Lords of Destruction

Death Dealer 3: Semi-enjoyable (?) train-wreck

I'm sure I will get around to book IV.

God speed James Silke!

Sunday, February 23, 2025

Some recent acquisitions

|

| The three other images below are postcard ads included w/Lee volume. |

|

| When My Body’s Numb and My Throat is Dry, I grab a Trooper. |

Friday, February 21, 2025

Paper books are better than digital: Five reasons why

Monday, February 17, 2025

Ardor on Aros, andrew j. offutt

|

| A cover better than the contents... unfortunately true of many Frazettas. |

(some spoilers follow)

The good

Great cover by Frank Frazetta, though unfortunately has nothing to do with the contents of the book (save perhaps symbolically, and I’m being generous).

It’s an easy, fast-paced read. Which says something for Offutt’s prose, which if not elevated or inspired does the job.

It’s unrepentant pastiche. Unlike some pastiches which dance uncomfortably with their source material, Ardor on Aros leans in all the way. The protagonist, Hank Ardor, is transported to Aros, a planet conjured from the imagination of three separate beings, one of whom is a female author writing a Burroughs pastiche. He arrives nude and is able to take huge leaps due to the thin atmosphere on the planet. We run into “Dejah Thoris” or someone closely approximating her; he names his two alien mounts “ERB” and “Kline”—the latter named after Otis Adelbert Kline, who wrote his own sword-and-planet including The Swordsman of Mars (1933) and The Outlaws of Mars (1933). Still not sure if this might not be better described as parody.

The bad

The pacing is off. It feels rushed, but not in a great barreling and breathless Burroughs manner. Too much emphasis on seemingly inconsequential details and not enough on important events.

Sexual assault and worse that will likely stop many readers dead in their tracks. Part of this is deliberate; the story attempts to tell a more “realistic” version of A Princess of Mars and what would happen were people walking around nude and taken captive by barbaric conquerors. But it’s still tough to digest.

It’s supposed to include the spicy sex ERB avoids but it’s almost as tame. The violence is more graphically described but it lacks ERBs style. In short, it doesn’t deliver what it says on the tin. The back cover trumpets, “what happens to a red-blooded young graduate looking for sex, fame, and answers when he suddenly finds himself naked, frightened, and several light years from earth? A lot.” Except, not really.

Can’t really recommend unless you’re an S&P completist.

Friday, February 7, 2025

Cold Sweat, Thin Lizzy

Wednesday, February 5, 2025

An interesting personal insight into Moorcock’s inspirations

Monday, February 3, 2025

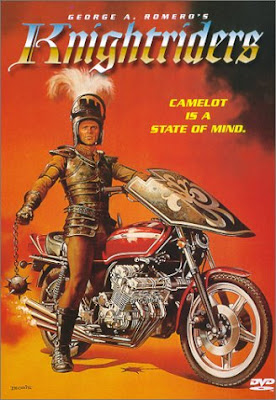

Knightriders, a review

(Warning: Spoilers)

Utopias cannot survive contact with the world of commerce. It’s a message delivered in brutal fashion in the catastrophic ending of George Romero’s Knightriders (1981). Idealism meets the hurtling steel of a freight truck, alternative counterculture going under the wheels of the unstoppable economic engine of the 1980s.

The outcome is predictable and sad. But the leadup and the message of the film is magic.

Weird and flawed, too on the nose perhaps with heavy-handed messaging, Knightriders nevertheless succeeds. It’s unpredictable, meaningful, wonderfully anti-establishment, and utterly singular.

The film opens with a knight (Ed Harris) waking up in a forest, naked and in the arms of his paramour. He kneels and prays over the hilt of his sword, enters a nearby pool to bathe … and proceeds to beat his back with a branch in what we can only presume to be some sort of purification ritual.

Right then you know you’re in for an offbeat movie. And if you had any doubts Knightriders goes straight off the deep end when instead of a horse Harris climbs on a motorcycle and rides back to “Camelot.”

Romero apparently got the idea for Knightriders from the violent medieval reenactments hosted by the Society of Creative Anachronism (SCA). He had planned on horses but producer Sam Arkoff told him to put his knights on motorbikes. The rest is history. Despite the obvious anachronisms it makes painstaking efforts toward medieval realism, from the forging of weapons, romance, and chivalric oaths sworn in fealty to a king, who is really only a man (and a flawed one at that) full of grand ideas and a vision of something better.

Knightriders engages with the myth of King Arthur in a very unique way, demonstrating the extreme malleability of the old stories. It skips the “historical” Arthur of the 5th/6th century and the romantic late medieval-ish setting of Excalibur and instead leaps straight into 1980. There are no knights, no nobles, no real king. The story instead follows a troupe of traveling entertainers who put on a combination renaissance fair and tournament, complete with jousting and full-on melee conducted by knights riding motorcycles. At its head is Billy (Harris), a stand-in for Arthur. He is the heart of this comic but earnest ragtag group of misfits.

Instead of Camelot Billy’s “kingdom” is a commune of outsiders, all wanting something different than the 20th century has to offer. It’s got some similarities with the hippie communes of the 60s, perhaps the last gasp on the verge of the decade of excess.

It wasn’t at all what I was expecting. I of course know Romero from Night of the Living Dead and its various sequels, and so I thought I might be getting ultraviolence, apocalypse, bloodshed. Knightriders is none of the above. There’s plenty of action, of course (the stunts are fantastic and I winced at a couple of the crashes--stuntmen hit the ground HARD. These guys were not making an easy paycheck). But its basically a character drama spread across a large troupe of actors. All of Romero’s old cronies are in the film … as I was watching every five minutes I was like, “wait, there’s the guy from Dawn of the Dead, and another guy from Dawn of the Dead. That’s the guy from Day of the Dead! Wait is that a Stephen King cameo?” (answer—yes.) Tom Savini plays a major role, not a villain but a foil to the king, and who knew—Savini can act. It’s got an interesting Merlin too, a dude with some medical training but equal parts witch doctor, harmonica playing savant, and prognosticator.

It’s amazing Knightriders ever got made, and unsurprisingly it was a commercial flop. Harris admits in a relatively recent interview that while he remains a fan he knew it was destined for obscurity. It’s too odd and offbeat, non-genre, and the intended audience is unclear. Truth be told it’s also flawed. Some of the acting is, to be charitable, pedestrian. The dialogue in many places is stilted. It’s at least 30-40 minutes too long and badly in need of an edit. It meanders and threatens to lose the thread of story.

But I can deal with these imperfections, even its deep and abiding flaws, for what we did get. Imperfection is the way of the world. The courage of knights wavers, their honor and fealty are tested by fortune and fame and lust, and often fail. This film does not fail, and for what it lacks in technical artistry it succeeds through heart. I can think of very few films as earnest and sincere. Romero set out to make a statement about the pressures to sell out vs. staying true to your art, and of the extraordinary difficulties of leading a principled life. Of living a values-led life, to whatever end.

I felt a deep stir of emotion near the end of the film when Harris/Billy/Arthur sees himself not on a bike, but a horse, galloping off on some quest through green lands in a better place. He passes on his legacy in the form of a sword, handing it to a wide-eyed young fan who wanted only an autograph but got much more.

Even if we cannot ever experience earthly utopia the elusive search continues. As long as nonconformists and artists and the disaffected yearn for something more, Camelot beckons.