Feeling optimistic after reading the introduction by none other than Roy Thomas, who appears to be “writing a story or three” for the relaunch.

"Wonder had gone away, and he had forgotten that all life is only a set of pictures in the brain, among which there is no difference betwixt those born of real things and those born of inward dreamings, and no cause to value the one above the other." --H.P. Lovecraft, The Silver Key

Feeling optimistic after reading the introduction by none other than Roy Thomas, who appears to be “writing a story or three” for the relaunch.

We don’t have infinite time. The amount of reading attention any new book must compete with is getting progressively smaller. So we have to be selective.

It’s basic math.

Robert E. Howard read Edgar Rice Burroughs and Jack London and H. Rider Haggard (and many, many authors besides, but bear with me as I make this point).

Michael Moorcock read Howard and his contemporaries C.L. Moore and Clark Ashton Smith… but is obligated to read ERB and London and Haggard.

Writers today read Moorcock and his contemporaries Karl Edward Wagner and Jack Vance and Poul Anderson. But also should read Howard and Moore and Smith … and ERB and London and Haggard.

The demands on new generations of readers multiply. What about readers and writers three generations from now?

Oh, and we all must read the classics. Shakespeare and Milton and Homer and Hemingway.

Make sure you read outside your genre. One should read history, too.

The accumulated reading, generation on generation, cannot continue. The math doesn’t add up. How many books can anyone read in a lifetime?

Some books must fall by the wayside.

This is just the beginning of the problem. We have many more demands on our attention than previous generations. Movies, TV, video games, TTRPGs, YouTube, doom scrolling, etc., all compete for our attention during “free” time. And despite all the breathless predictions of the techno utopians, we don’t seem to be working any fewer hours.

That means we’ve got choices to make. As you get older, you realize you cannot fritter your time away. It’s far too precious.

So, what are we to do?

My advice: Read what you want. Just read, as long as its not Reddit forums or Twitter threads.

Read new sword-and-sorcery or read the classics. Read comic books, or graphic novels. Just make sure it’s something someone has created, with care.

Don’t listen to what other people think. I don’t. Because I’ve read enough to spot illogic and ad hominem and the rest.

Just because a book is old, published 60 or 80 or 400 years ago, does not render it out of date. C.S. Lewis tells us to rid yourself of “the uncritical acceptance of the intellectual climate common to our own age and the assumption that whatever has gone out of date is on that account discredited. You must find out why it went out of date. Was it ever refuted (and if so by whom, where, and how conclusively) or did it merely die away as fashions do? If the latter, this tells us nothing about its truth or falsehood.”

And our age is prone to its own illusions.

Anything still in print 60 years after it was published is probably worth your time. Because it survived the test of time. The books that influenced your favorite author(s) are probably worth reading too, even if out of print.

But don’t feel obligated to plow through classics that are going to kill your love of reading, either.

Read what interests you, and carry that fire against public opinion. Which is often shit.

That’s another benefit of reading widely and deeply—read enough good stuff and you’ll develop a sensitive and accurate bullshit detection meter.

|

| Issue 29 TOC. |

|

| That map made me a child of sorcery... |

|

| Conan's Ladies... easy on the eye. |

|

| Holy balls that's some good artwork... Almuric at left (Tim Conrad) |

|

| I desperately wanted to participate. |

|

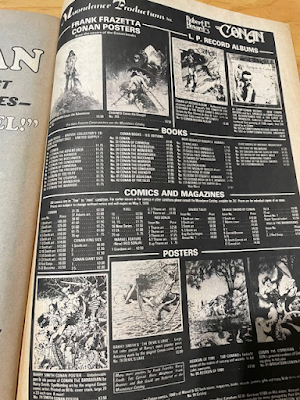

| Would they still honor these prices? |

|

| RIP John Verpoorten. I'd read every article, regardless of subject matter. |

|

| Swords and Scrolls... first letter by one Andrew J. Offutt. With praise for issue #24 and "Tower of the Elephant." |

|

| Two towers, old and new. |

The former represents the creative forces of chaos. The latter the ordered forces of law.

It’s a very yin-yang, or Moorcockian, way of looking at things.

The older I get I see the need for both. For tradition, and for change. Both in life, and in art. Perhaps you’ll find this a milquetoast viewpoint, and want more sturm un drang. But not today. I’m feeling reflective.

Defenders of the old see what the masters have done and want that to stand, immobile and fixed, like some mountain. It was great, it still is, why change it?

Proponents of the new see old art and admire some aspects of it, but believe that it no longer reflects present realities. And wish to carve new stone out of the existing material, or make something else alongside it.

I see a lot of angst over this divide, but believe these seemingly opposing forces can be reconciled. Because we need both.

I believe our present culture is entirely too much focused on the new and shiny. And not enough on learning from the brilliant minds who have come before us and did some things better than we do. There is so much to be gleaned from history. Much of what we think of as new has been done before. So don’t confuse looking backwards with a backwards mindset.

But I also recognize change as inevitable, and often results in forward progress. Doing the same thing over and over again results in staleness and conformity. S&S grew moribund in the latter 70s and collapsed in the 80s. The New Wave of SF and its dangerous visions broke away from the hard SF that was itself popular and groundbreaking in the early 20th century, but had become fixed and rigid. And the 60s and 70s saw amazing new works created.

Change is inevitable. It’s always been with us. If you don’t believe so, you might look at H.P. Lovecraft, who broke from the old gothics and ghost stories with his radical new extradimensional horror, or Steven King, who added a blue-collar pop sensibility and more humanity to Lovecraft.

Of course, merely because something is new or subversive doesn’t make it good. Nor does critique of your subversive project mean a bunch of old farts “just can’t handle it.” It just might mean the art was poorly executed. There was a lot of bad old art in the past that was once new, but has been forgotten and discarded. No one remembers most of the authors working in Weird Tales. But those that have lasted have much to teach us.

It’s cool to make new stuff by recombining old things.

It’s OK to love old school stuff, even to repeat or pastiche its forms.

We can have it all. No one is getting hurt by the conservative impulse to preserve, or the liberal urge to subvert.

Where do I fall, preferentially, on this spectrum?

To no one’s surprise I’m a small c conservative when it comes to art. I enjoy some subversive art, and admire the creators who challenge the status quo with potent new visions. Though I find myself preferring subversive material that is old enough to have passed into acceptable territory again. See Elric, or bits of The Once and Future King.

But my deepest sympathies lie with old fiction. Robert E. Howard and J.R.R. Tolkien remain two of my literary lodestars, and always will. I don’t see them as old. I still see them as innovators who broke new ground from old sources, who had their influences but took them and made something wholly original. Powerful enough to spawn imitators, and genres.

In “Beowulf: The Monsters and the Critics,” Tolkien chided the literary critics who sought to study Beowulf by reducing it to its component parts, and in so doing, broke it. Pulled down the old tower turning over stones, not realizing from the top you could see the sea.

But if Tolkien had only looked at and admired the past we wouldn’t have The Lord of the Rings. He also made something new from old legends, and broke new ground, though his own powerful creative impulse.

Karash Khan left but a single watcher to mind the Cimmerian. This thankless task fell to the youngest of the nine Sicari, a quick-eyed Turanian not much older than twenty. No one knew his given name, but his brothers called him Badish Khan. Bred in the alleys of Sultanapur, when the Master found him he was already a hired knife at fourteen with more kills than throat-slitters thrice his age. He was like an ingot of iron, crude and without form; while Karash Khan was the hammer, it was dark Erlik who provided the flame.

Even so, the Sicari could not withstand the Cimmerian’s berserk fury. Death might have been their master, but neither god nor man could master this wolf of the North. His god was Crom, grim and savage, who gave a man the power to strive and slay and little else. And when he called upon Crom, it was not in prayer or benediction . . . it was so the dark lord of the mound might bear witness.

Among southern nations, Conan had seen madness dismissed: a disease physicians sought to cure, a weakness learned philosophers debated in shaded courts. Madmen were broken men, they said, who could hope for no better than a quick and quiet death. Among the barbarians of the north, however, madness was something else – a thinning of the veil between worlds, a harbinger of doom, or the curse-gift of that fey and feral goddess, Morrigan. The Cimmerians held madmen apart from others, their ramblings fraught with the truths of a perilous world.