Tom Shippey might be the closest connection we have to J.R.R. Tolkien himself, save for Tolkien’s son Christopher. Shippey met Tolkien and had a few conversations with him shortly before the latter’s death in 1973. He followed in Tolkien’s footsteps as a professor of Anglo-Saxon literature, inheriting Tolkien’s chair and syllabus. Most importantly of all he understands the source material of Tolkien’s legendarium probably better than any man alive, including works like the Finnish

Kalevala, Beowulf, the Eddas, and the Icelandic sagas. Shippey has also written two highly regarded critical works on Tolkien (certainly the two most impressive I’ve read),

J.R.R. Tolkien: Author of the Century and

The Road to Middle-earth: How J.R.R. Tolkien created a new mythology.

Entering Friday’s night’s Boskone 47 conference at the Westin Boston Waterfront in Boston, MA, I was hoping to steal a minute or two of Shippey’s time to ask him some questions about my favorite author. I’m pleased to say I got much more!

I arrived at the conference a little before 6 p.m., checked in and got my badge and conference literature, then slid into an ongoing panel discussion about works of science fiction that don’t seem to be aging well (“What’s Showing Its Age?” by Daniel Dern, David Hartwell, and Peter Weston). The session let out at 7, just in time for an autographing session with Shippey, children’s author Jane Yolen, and sci-fi author Andrew Zimmerman Jones. The autographing session was being held in the Galleria, a large exhibition hall full of book dealers, purveyors of fantasy sculpture and miniatures, original artwork by the likes of John Picacio and Michael Whelan (the latter of

Elric book cover fame), and much more.

When I entered the hall I saw that Yolen had a line of some 15-20 people deep waiting for autographs; Shippey had only a couple! Within minutes I was shaking the hand of perhaps the greatest Tolkien scholar ever, offering thanks for teaching me more about Tolkien than any other author, and garnering signatures for my copies of

J.R.R. Tolkien: Author of the Century and

The Road to Middle-earth.

I was prepared to be swept aside by other autograph seekers, but with none coming I got to speak with Shippey for quite a while. I felt completely out of my depth and initially a bit flustered, but he put me at ease with his friendly banter, warmth, and genuine sense of humor. Shippey is a lifelong fan of fantasy and science-fiction beyond Tolkien which also helped put me at ease.

I could not resist asking such fannish questions as:

“What was Tolkien like?”

“Have you read Michael Moorcock’s

Epic Pooh? What did you think?”

“Which was a greater influence on Middle-earth: Old Northern or Christian mythology?” (this last question sparked some interesting side-conversation on Joseph Pearce’s

Tolkien: Man and Myth).

“Was Middle-earth our actual earth in some pre-cataclysmic age? Or did Tolkien intend it purely as a fictional creation?” (The former, Shippey said)

Shippey took the time to answer them all. I won’t share all of Shippey’s comments here as it was personal, candid conversation, but I will relay a few things. For example, he mentioned how Tolkien was very Hobbit-like: He cared about things like football scores and people’s names and their origins. Shippey also talked about the declining enrollment of English majors and the marginalization of literature studies and critics (I agree completely). It’s strange to say, but having spoken with Shippey I now feel two degrees removed from Tolkien himself (and technically, I now am)!

Afterwards I attended two panel discussions featuring Shippey and others:

The Lord of the Rings Films: 5 Years Later (which ran from 8-9 p.m.) and

The Problem of Glorfindel and Other Issues in Tolkien (which ran from 9-10 p.m.). These were very enjoyable.

In general, Shippey enjoyed the Peter Jackson films and thought they were well done. He has some problems with them, of course, and stated that he didn’t like what Jackson did with the character of Theoden. Aragorn’s fake death when he falls over the cliff was derided by the panel, as were some of Jackson’s over-the-top scenes of grue (his horror influences spilling through).

But in general the panel thought the films were very good, and that the changes from the book were necessary in adapting it to a film medium while ensuring that the movie remained profitable and accessible for a broader audience. Someone else asked why battle scenes were downplayed in the books, particularly their graphic details, while in contrast the battles were huge set-pieces in the movies. Shippey responded, “Everyone who Tolkien knew was a veteran—there were things you didn’t have to explain,” whereas audiences today are “civilianized.”

Speaking of profitable, Shippey quipped that Tolkien’s writing of

The Lord of the Rings “must have been the biggest return on investment in the history of the universe,” noting that Tolkien used scrap paper and borrowed ink to write the early drafts, and only had to sacrifice a college professor’s spare time (which is essentially worth zero, joked Shippey, who is a professor himself).

Shippey said Jackson made some “very gutty decisions” with the script, including leaving the ending as-is, keeping its tone of sadness and loss when a

Star Wars-like ending might have been more palatable for a modern audience. Fellow panelist Michael Swanwick commented that the end of

The Lord of the Rings “breaks your heart,” in that it’s happy and sad all at once. One of my favorite moments was Shippey’s comment that Sam’s final line (“Well, I’m back”) is “such an Anglo-Saxon thing to say:” It’s all of three syllables and in one respect pointless (of course Sam is back!), but at the same time means so much more. Shippey noted that Sam paradoxically came back to die, but also to live with his family and as Mayor of Michel Delving.

The panel took some questions from the audience, including one from yours truly about the decision to remove the Scouring of the Shire. Other panelists than Shippey weighed in, but the general consensus was that there were already too many endings and that the Scouring was anti-climactic and works better in a book than on film (I don’t really agree, but there you have it).

As for whether or not these films still resonate, a member of the audience pretty much answered that with a story about a trip to New Zealand taken by his friend and friend’s fiancé. The two were pleased to discover that the country’s tourist maps are marked with all the sites from the films. The couple hiked up “Mount Doom” and brought him back a piece of igneous rock from its now legendary slope.

The second lecture/panel discussion I attended,

The Problem of Glorfindel and Other Issues in Tolkien was a discussion of the minutea in Tolkien’s legendarium and some of its seeming inconsistencies. Panelist Mary Kay Kate of the Mythopoeic Society commented that, “We care about trivial things because [Tolkien] succeeded so well at creating his world—he can’t have just made mistakes.”

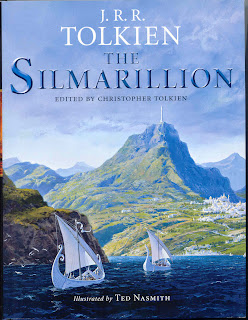

The panel opened with a discussion of Glorfindel. Elves in Tolkien’s legendarium do not reuse names, therefore the Glorfindel who died fighting a balrog in the First Age (as told in The Silmarillion) must have been reincarnated into the Glorfindel we know from

The Lord of the Rings. However, it was unclear (and remains so) if Tolkien intended this, or whether he merely re-used an old name by accident. Shippey remarked that Tolkien had an uneasy attitude toward reincarnation—while he didn’t deny it, when asked whether he believed in its possibility Tolkien answered, “I’m a Catholic.”

There was a lot of conversation among the panel and the audience regarding Tom Bombadil, why this section of the book feels different, whether or not it’s important to advancement of the plot, etc. I admit that I’m rather ambivalent about this section of the book and so took few notes.

Shippey, who had been quiet for much of this discussion, then took off on a spellbinding 10 minute talk about Tolkien’s lifelong habit of revising and re-revising his work: “Niggling,” Shippey called it (Tolkien wrote a story entitled “Leaf by Niggle” which addresses this facet of his personality). This led to some problems and could have potentially wrought significant havoc with Tolkien’s creations. For example, Shippey stated that Tolkien was strongly considering a sixth revision of

The Hobbit which would have significantly altered and softened the story, but fortunately reconsidered when a confidant said, “That’s all well and good John Ronald, but it’s not

The Hobbit”). Shippey added that Christopher Tolkien told him that “his father never would have finished

The Lord of the Rings if it were not for C.S. Lewis.” Shippey also noted that Tolkien went a large part of his latter academic career without publishing any scholarly works or papers, which was frowned upon by administration.

Perhaps the most interesting part of the session was the panel’s discussion of the problem of orcs. Some critics have called Tolkien’s depiction of the orcs racist; also troubling is the fact that orcs seem like an unredeemable race (whereas others in Tolkien’s legendarium choose evil, so they can theoretically repent their ways and be granted mercy).

Shippey noted that orcs share many human-like values: For instance, they value loyalty and abide by rough Geneva-like conventions of warfare (Shippey quoted the “regular elvish trick” line from the orc Gorbag who finds Frodo bound in webs and abandoned on the orc-path; Gorbag is at least outwardly appalled that a soldier would leave a wounded fellow soldier to die). “Orcs are all right!” Shippey said. But he also laid his finger on the root of the orcs’ evil: The problem of Ufthak. Ufthak was the unfortunate orc who was found by his comrades alive, emeshed in Shelob’s webs. Rather than freeing him, the other orcs laughed and left him hanging in a corner to die a horrible end. Saving him wasn’t their business.

Shippey made a compelling case that the problem of Ufthak demonstrates that the orcs have a thoroughly modern mindset: They know the difference between right and wrong and have a theoretical knowledge of good and evil, but don’t put into practice. They act self-centeredly, separate from standards of decency. This attitude resulted in the major man-made holocausts of the 20th century.

On a final note, when the moderator asked the panelists for closing remarks, Shippey with his booming voice told everyone that Tom Bombadil is “not a Maiar, or a Valar. He’s a land wight!”

Sounds reasonable to me, and who am I to argue?